“Singles by The Moody Blues were a rarity, so growing up on a diet of Radio 1’s early ’70s playlist, my exposure to the Moodies had been almost non-existent”, says TPA’s Geoff Ford. “My imagination was captured, in 1972, by the release of Isn’t Life Strange, a John Lodge composition from the classic Moodies line-up’s seventh album, Seventh Sojourn, and then the reissue of Nights in White Satin. I subsequently devoured their back catalogue with great vigour, and that, in turn, led me to a whole new world of music that never got close to Radio 1. I was, therefore, delighted to review John Lodge’s recent live offering The Royal Affair and After and to speak to John about this new album and those early pioneering days.

It was a privilege to have covered the Night of Stars concert at Birmingham Symphony Hall, for TPA, some three years ago, although I had to miss the end of the show to catch my last train home…

“I hadn’t realised that we were only supposed to do an hour,” John laughs, “but all the fans were there and they’d paid! Somebody whispered in my ear that maybe we should stop, now…”, he laughs again. “Sometimes in the seventies, we would sometimes do two and a half, or three, hours!”

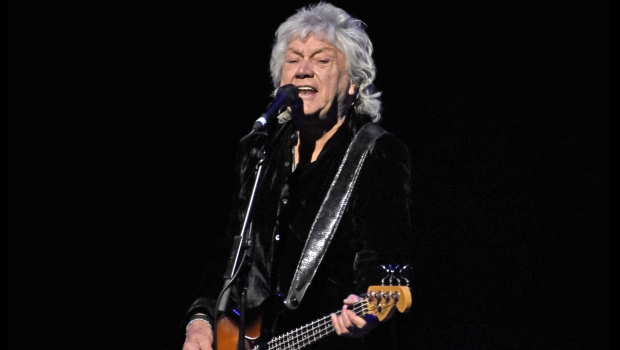

The Moody Blues’ singer, songwriter and bass player, John Lodge had played the headline set on an evening when Birmingham recognised the achievements of two of the city’s greatest musicians, himself and Carl Palmer. “Yeah! If you wanna play, you wanna play!”

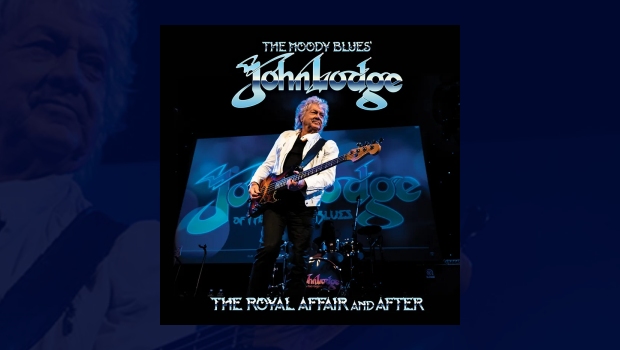

The new album, I told John, had brought back tremendous memories of that night, which came just weeks before these new recordings from the Las Vegas concert on The Royal Affair Tour.

“Thank you. We had a fantastic time on the tour with Yes and Carl and Arthur (Brown), it was a great tour. We didn’t know Covid was coming and it was just fortunate, really, that we recorded this concert in Las Vegas.”

Being on tour with Yes introduced John to their lead singer Jon Davison who was invited to sing lead on John’s composition Ride My See-Saw and Justin Hayward’s iconic Nights in White Satin on these recordings.

“His vocals, they’re fantastic and I’m really, really pleased!” John enthused. “It’s great to have Jon on stage with me. I said to him ‘Come on, Jon, you can sing Nights,’ and I think he makes it his own. Jon’s here with me, right now, and we’re just discussing a few things. And the more-solid arrangements, which (musical director) Alan Hewitt has done on the strings, I think are wonderful.”

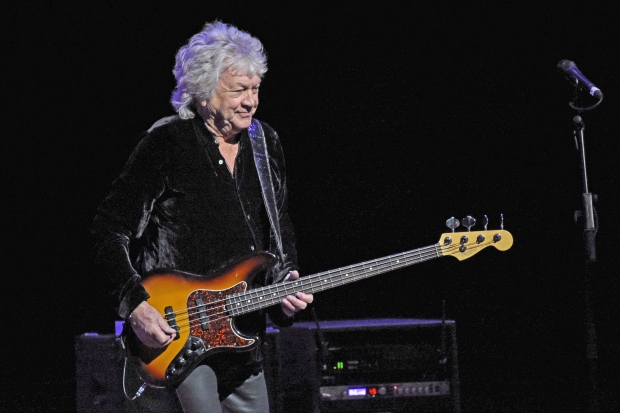

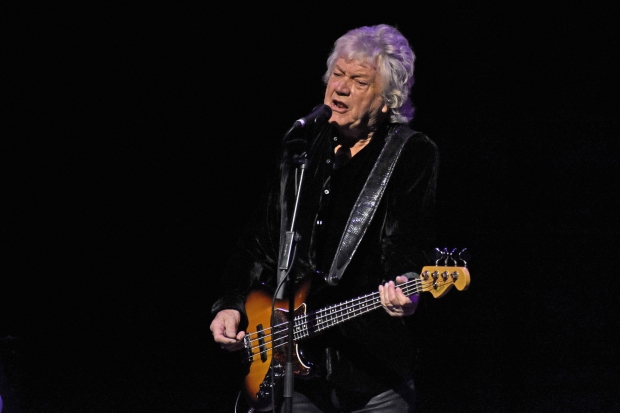

One of the stand out features of the album is John’s punchy bass and the energy that brings to the live performance. This kicks in right from the outset with Stepping in A Slide Zone.

“We had fun doing that. When I realised… It’s really difficult when you are the artist as you don’t get to hear the song because you’re singing or playing bass. You never actually hear it in your ears and so, when we started mixing it and I heard the tracks from the recording, I thought ‘Wow! This really rocks!’

“I said to the guys in the band, when we were rehearsing before the tour, what I really want is to get the engine room of the band driving these songs and Billy Ashbaugh, my drummer, is fantastic. He and I talked about the bass drum and the bass really driving but keeping all the emotions of The Moody Blues. There’s a way of doing it like the 1812 Overture: you can make it really big and you can make it really small but it’s still got the energy, that’s what I want to do on stage, I want to keep that energy flowing.”

The Royal Affair and After is a really great snapshot of John’s desire to ‘keep The Moody Blues’ music alive’, which is admirable. The cello of Jason Charboneau is full of atmosphere and perfectly captures all of Mike Pinder’s original keyboard parts.

“Absolutely,” John agrees. “It’s fantastic. When I put the band together, I was thinking I’d always loved the cello. I wasn’t a cellist but I can work my brain around it. I played cello on Ride My See-Saw, with the Moodies, and a couple of tracks on the next album. Ray Thomas was such a great friend of mine and an integral part of The Moody Blues’ music and I didn’t want to replace him with someone else playing poor Ray’s stuff. I thought if I can get the right cellist, I’m sure he can play all the flute parts on cello but also add the driving parts that cellos do in an orchestra. And with Jason, I’ve found the person who knows how to do the subtle parts and the flute parts but also drive the cello from the bottom. It’s a wonderful thing during rehearsals – because he’s rehearsing all the while! We used to say, in the Moodies, with the Mellotron you’ve got to capture the zeds and the zed parts of the cello drive the songs along.”

John’s signature song is Isn’t Life Strange. The live recording is sublime and the song has grown and matured with age over the past 50 years.

“It has and I’m always looking for something more. ‘Where does this song take you?’ That song, for me, was the ultimate 1812. We’ve done a few subtle changes. Since I wrote Isn’t Life Strange, all those years ago, I’m always looking at it thinking ‘Is there something more in the song?’ I’m thinking with this band, with Alan and Jason and Duffy (King) on guitar, we explore this song almost to the nth degree, more than ever before.”

Along with some of John’s own compositions, the live set features, as a tribute, a track written by each of his Moody Blues bandmates: Mike Pinder, the late Ray Thomas, Justin Hayward and Graeme Edge, who sadly passed away just days before the live album was released. Whilst each song was credited to an individual, all of the band members had an input to every song, each track was a true band collaboration.

“Yes,” says John, “each song was a musical collaboration. When any of us wrote a song we would go into the studio and we would sit around this coffee table with a brown fluffy carpet on the top. We’ve still got the coffee table in storage, that table could tell some stories!

“When we played the other guys a new song, we would all think about what we wanted to do with the song – and then it became a Moody Blues song. It was important for all us to give each other respect and respect for the song. Everyone had their input to the song and so they could all say ‘This is my song,’ as well. It was really important for the Moodies on those first seven albums and for the next two. It was really important that everybody felt they were a part of every song.

“Alan Hewitt and I discussed the running order to make it really work and putting in the songs from the other guys in the band, the tributes, in the right place, the right balance for the concert.”

Through his work with the Moodies, John Lodge became a hugely influential bass player. In the mid-’60s it was unusual for the bass guitar to do more than just fill out the bottom end or keep the beat of a song. John’s forward-looking playing helped to change that.

“There are two basic ways of playing the bass,” he explained, “You can stick with the basic roots of the songs, there’s nothing wrong with that, it always drives the song along, or you can try and find a bass part that is the song itself, so that you can recognise the song, without anyone else playing, just the bass.

“Carol Kaye (Phil Spector, The Beach Boys and many others), Jamie Jamerson at Motown: when you heard the bass line of a Tamla Motown song, you could sing along with the song. It’s the melody within the bass part, a sort of combination of bass and cello. I love exploring bass parts and finding what bass part will go with a song.”

Given the musicality in John’s playing, even at the beginning of his Moodies career, I wondered about his own musical influences and if classical music had played a part?

“I didn’t really have any musical background until I was 13. When I was 8, 9 and 10, my junior school used to have what was called a rest period where the teacher used to play a classical record. Really, I think it was to give the teacher some time off from the kids,” he laughs. “Possibly, that entered my psyche? I don’t know but I really got interested when rock and roll came along.

“I saw Rock Around the Clock when I was about 12 years of age and The Girl Can’t Help It and something just struck me, I wanted to be a part of this. This was at the same time as people like Tommy Steele and Chas McDevitt and the skiffle bands. I thought how on earth can I learn to be a musician?

“So, I listened to all the skiffle songs and bought a guitar from a neighbour – or my mum did, for about five pounds. It was a steel-strung acoustic guitar and I started to learn these one-chord songs from the skiffle days, Freight Train and Cottonfields, things like that, but I realised skiffle wasn’t where I was going because it was rock and roll that interested me.

“There was a café by my school when I was 13 and they had a Rock-Ola juke box in there. Every lunch time I’d drop my lunch money in the slot, have a coffee, and play every record I could. I realised I was listening to the left-hand side of the piano: people like Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, all left-hand boogie and that was what intrigued me as it drove all these songs along. They didn’t have basses at that time but I started to learn the bass lines, the boogie, on the bottom four strings of my guitar.

“I bought an electric guitar and then found an electric bass, a Tuxedo Bass. It was really unwieldy and hard to play. Then, one Saturday morning I went to my music store, Jack Woodruff’s in Birmingham, and there in the window, there it was: ‘Direct From America – Fender Precision Sunburst Bass.’ And that was it!

“I remember going home and saying to my father, ‘Dad, you’ve got to help me, again. I’ll pay you back one day!’

“We went back into Birmingham, my dad signed the papers and I bought the Fender Precision Bass. It’s played on nearly every Moody Blues song I’ve ever recorded. I still use it now to record the songs I’ve been releasing lately, although not the live versions. I’ve been using that bass because it plays on its own, it’s a beautiful bass. It was incredibly expensive, at the time. It was, like, £115 and you could buy a Mini car for £490.”

I suggested that that bass doesn’t owe John anything, now.

“Oh, no, it doesn’t! Every time I pick that bass up, do you know, I can still smell the bass from the day when I bought it. It’s a really incredible memory.”

John famously first met his future Moody Blues’ band mate Ray Thomas on a bus, as a teenager. Their conversation led to them forming a band together, El Riot and the Rebels, a band which would also see Mike Pinder pass through its ranks.

While John continued with his college studies, Ray became a founder member of The Moody Blues. With a 1965 number 1 single under their belt, the band failed to follow up and, by mid-1966, only Thomas, Pinder and Edge remained of the original line-up. Their future prospects appeared less than rosy.

“They’d had Go Now! of course,” says John, “the wonderful Bessie Banks song, and then I don’t know what happened to them after that, to be honest, because that was a big hit. I just don’t know what happened, I was busy doing other things.

“I finished college and Ray Thomas rang me, one day. Ray said ‘Hey, Rocker, have you finished college, yet?’

“I said ‘Yeah. I’ve just finished.’

“‘Get down to London,’ he said and that was it!

“I went down to London, I think it was June 1966. I met up with Ray again, also Mike Pinder, who I’d know from the band we had before, and I met Graeme who I knew anyway, from a band called Jerry Levine and the Ventures.

“I spoke to Mike first, I stayed in Mike’s flat in London. He’d written a couple of songs and he said they want to write their own songs, they didn’t want to record other people’s songs. That was fine by me because for five years before that I’d played every rock and roll song there was, all coming out of America.

“I thought ‘Yes!’ I really wanted to be writing and releasing songs. That’s what we all wanted. Justin (Hayward, who joined the Moodies at around the same time as John) was a song writer, Ray was writing songs and that really appealed to me, we were all going to write our own songs.

“Everyone contributed in equal measure. That was the great thing about the band, we all contributed. It was the best part of it because everybody was there and there were no outside influences. It was just down to us to come up with the songs.”

The Moody Blues’ label, Decca, heard some of their songs and offered them the chance to record a demonstration album to promote their new Deramic Sound System, in return for waiving several thousands of pounds of outstanding advances. The result was Days of Future Passed with Moody Blues’ songs taking the listener through the course of a day. The songs were linked by orchestral passages performed by The London Festival Orchestra conducted by Peter Knight.

Originally released as a budget-priced album, as Days of Future Passed gained popularity it was repackaged as a full-priced album, introducing The Moody Blues to an adoring transatlantic audience and cast the die for successes beyond their wildest dreams.

“It was just a fantastic time, you know?” John reflects. “We were young, no barriers, ‘Let’s just do it!’ We didn’t take no for an answer and we went to the record company and said we wanted to record 24 hours a day. No one had ever done that before us, as far as I know. And the record company chairman, Sir Edward Lewis, said ‘Yes, fine, whatever you want to do.’

“That was amazing because, as far as I was concerned, we were pushing the boundaries of progressive music, really. We weren’t going along the AM road, the pop route, it was another road altogether. We told the record company that we were not interested in releasing singles from our albums. If they wanted to do that, it was up to them. We wanted the albums to represent The Moody Blues at that particular time and there were a couple of albums where we didn’t release a single.”

Revolutionary ideas at the time and The Moody Blues would soon become one of the first artists to launch their own label, giving them even greater control of their musical output. In the space of just two or three years, The Moody Blues re-wrote the rule book and changed the musical landscape for so many artists who followed in their wake.

[You can read Geoff Ford’s’ review of The Royal Affair And After HERE.

Live photographs by Geoff Ford.]