Back in the days of the tabloid-sized music weeklies, or “inkies” as they were known, for a period from the mid ’70s until the early ’80s the NME was my music Bible. It was The Guardian to the Melody Maker’s Telegraph, and to Sounds’ The Sun. That will mean little to anyone outside the U.K., suffice to say it was much more cutting edge than the fusty and dusty old MM, and way more intelligent than the populist Sounds. With writers like Nick Kent and Charles Shaar Murray, and occasional guest pieces by the daddy of rock journos, the mighty Lester Bangs, it brought to life the unattainable and otherwise unknowable seedy underbelly of rock’n’roll in those very pre-internet days.

In 1977 a young whippersnapper by the name of Paul Morley joined the NME, and together with his brainiac comrade-in-arms Ian Penman they began to slowly dominate the writing of the paper with their dense and impenetrable prose. With their references to obscure philosophy, social theory, and use of critical theory, their reviews and interviews often spent far longer on pseudo-intellectual discourse, or self-centred egocentric ramblings than the subject in hand, a Thesaurus never far from reach. Pseuds’ Corner wasn’t big enough to contain these two, thus alienating a big chunk of the readership, leading to the paper losing around half its circulation by the mid-’80s, me included.

The typically esoterically titled Zang Tuum Tumb, or ZTT, the record label he ran with Trevor Horn from 1983, with its arch and knowing style, often deliberately pretentious, summed up the Manchester miserablist’s outlook, although I will admit they put out some great music. While I tap away at the keyboard right now, I’m listening to the Andrew Poppy box set, On Zang Tuum Tumb, a fabulous meeting of modern classical music and the Fairlight, that should not work but does.

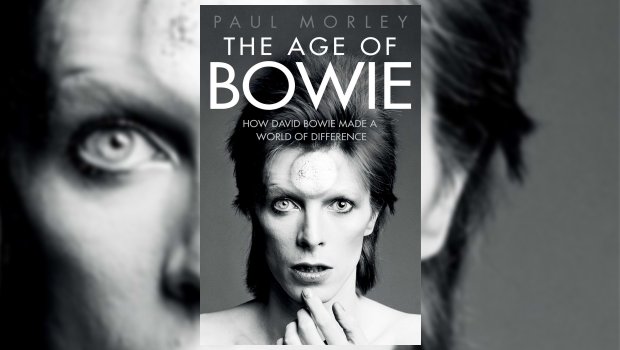

I have come across the permanently gloomy countenance of the author of this tome a few times on late night TV arts shows and read a few of his newspaper articles since those heady days, and he doesn’t seem to have changed much, viewing the world like it’s something he just stepped in, or at least that’s the impression given. I can’t ever recall seeing him smile, can you? Therefore, you can imagine my delight when I saw that Morley had written a book on his hero David Bowie, published a mere six months after the death of our generation’s John Lennon. I asked my better half to put it on my Xmas present list, and I’m glad I did, not necessarily for the reason you might assume given my dislike of the author!

Part eulogy, part biography, part social study, and inevitably part Joycean ego-ramble, The Age of Bowie takes 68 pages to actually get going, but there are a few acute observations buried in the untrammelled verbosity of the long-winded introduction. These occasional buried jewels are aided by the fact that Morley is obviously a big fan, and his love and enthusiasm for his subject is obvious. As a “for instance”, Bowie’s death affected me more than any in the rock’n’roll firmament since the passing of John Peel, but I’m not a big enough fan to have noticed as Morley did, that * (Blackstar) was Bowie’s 27th album if you count the two Tin Machine releases, and thus those before it represent an ‘A to Z’, with * being a new beginning that sadly became a full stop only a couple of days after the album’s release. Of course, that is all conjecture, but knowing Mr Jones’ way with media manipulation, the * was probably intentional and just as Morley called it.

A significant part of Morley’s forest of words in those introductory 68 pages describe his reaction to Bowie’s death, in one instance musing on whether or not to use part of his contribution to the Victoria and Albert museum’s 2013 exhibition David Bowie is as a eulogy he could give out to enquirers from the media who it seemed descended on the author like crows on a rubbish tip almost as soon as Bowie’s death became known to the wider world. This pondering results in sentences like this: “It was also a way of moving between and connecting all the Bowies there were – glam Bowie, tabloid Bowie, experimental Bowie, mad Bowie, mod Bowie, lurid Bowie…(followed by 18 (!) more Bowies)…and then ending with “…my Bowie, and amidst all these fragmented Bowies, fragmented Bowie.”

Then there are the intermittent pages of short sentences spaced as paragraphs dotted through the book, telling us what Mr Bowie “is” in unrelenting fashion, no doubt recalling that V&A exhibition:

Etc etc, all neatly line spaced and covering two pages, ending with…

(I may have made that last one up.)

I would bet everyone apart from Morley’s nearest and dearest, and his long-suffering editor, assuming he had one, skim read those! Yes, it sure is overly wordy in places, but this is Paul Morley, so what do we expect?

Page 69 reveals the start of the third chapter entitled Madness and beauty, and with it the beginning of the biographical section, and for me as a less than fanatical camp follower this is where it gets interesting for someone who has not read any other Bowie biography. The biographical detail in the book makes for a fascinating read, and you can forgive Morley’s occasional flights of conjecture as a result, as for the most part the analysis of the fast changing ’60s and the way Bowie interacted with them, and his unstoppable ambition in the face of numerous setbacks and false starts is highly astute.

Morley describes Bowie’s relationships with the important people in his professional life with an odd superficiality, and gets to the heart of his various collaborations with significant influences, managers, producers, and important bandmates in an unusually brief and cursory manner given his reputation for endless windbaggery, even to the point where a tad more insight might have been a good idea, especially where Mick Ronson and Tony Visconti are concerned. We end the book really none the wiser as to Bowie’s working relationships with those two highly significant colleagues.

Although he was only a handful of years younger than the prime movers in the Beatles, the Stones and the Kinks, Bowie was never a child of the ’60s, a place where most seemed to be under a naive delusion that everything will be OK if you only just let it all hang out, maan. No it won’t, it always inevitably ends in Altamont. No, Bowie was far more suited to the fractured and fractious ’70s where he performed the role of the cracked actor staring into a dark mirror that reflected all his numerous flawed characters, and with them the paranoia, glitz and sheer fucked-upness of that polluted decade right back at us via whichever costume or mask he happened to be wearing at the time. Bowie’s appearance on the Dick Cavett show in 1974 as a cocaine ravaged skeleton in a baggy suit elicits this from Morley: “It looks as though he was the result of a coupling between a ghost and a sewing machine”. You can gather from that that Morley manages to keep the fanboy sycophancy to a minimum!

David Bowie shone his multi-faceted persona on those of us who went through the biggest part of our teenage years at some point in that decade, Morley being one of those pubescent urchins, as was I, and we understand all of this.

That each year of the seventies and 1980 gets its own chapter, and the time before and after is summarised in a more condensed fashion is no contrivance, for Bowie WAS the 1970s writ large, whether or not you were into his music. These chapters are split into 140 numbered sections across the eleven years, revisiting “David Bowie is…” by commencing each section “He is…” It does get a tad wearing after a while, and some of the sections seem arbitrarily separated, continuing a theme from previously with no real justification for a new sub-chapter, but the wealth of detail and Morley’s meaty analysis overcome this contrivance.

Following the 1970-1980 immersion is an extract from Morley’s time at the aforementioned V&A exhibition where he was “writer in residence”, and was asked to write a book on Bowie in situ, as a kind of living art installation. To help with this he gave out cards to exhibition visitors asking three simple questions. These are my answers to those questions, the first of which I have changed from the present to the past tense, for obvious reasons:

My favourite thing about David Bowie was: The way he never stayed the same, always going through ch-ch-changes.

I first knew about David Bowie in: Probably 1972, Ziggy on Top of the Pops, but I only really got into him when Low came out, and it is probably still my favourite Bowie album.

I would describe myself as: A very interested onlooker, but not a fan.

You may have possibly got the impression at the start of this ramble that I came to bury the author, but by the time I got to the end of The Age Of Bowie, .I can only grudgingly praise him despite his untrammelled verbosity. If you only ever buy one book on David Bowie, it may as well be this one, but you will need a surfeit of stamina and a machete to negotiate the verbal jungle, and the patience of a saint to forgive the author’s overbearing self-regard.

ADDITIONAL INFO

Publisher: Simon & Schuster UK

Year of Release: 2016