Throughout his work in no-man and also as a solo artist, Tim Bowness exudes quality and class. A man who rarely steps into the limelight, and when he does, some might say with a little reluctance, he remains a musician who commands the respect of the community of progressive music icons.

Lost In The Ghost Light [reviewed HERE], his third album for Inside Out, has a fascinating concept, one which Tim was happy to talk about at length in this interview with Mike Ainscoe, although his opening remark, “I’ve just been talking to your wife!” might be the strangest start to an interview Mike has ever had!

Once the mix-up over a late change of phone numbers was resolved, we got around to talking about the concept and the themes of the album which have had quite an interesting gestation, all based on an encounter with someone he’s described as…

“…a sixty something jogger in an expensive tracksuit rifling through the vegetable racks at my local Co-Op. There was just something about the guy; he could well have been in any kind of band from like Stackridge or any veteran rock band he’d once played with.”

A suggestion even of Thotch?

“He probably was the lead guitarist on their first three albums.”

It was the point at which he started thinking about the moment when music first came into this person’s life and whether it still informed his music making, and music making in general, in the present day.

“It was a deliberate choice in choosing someone fifteen to twenty years older than I was because it was a very different experience in the music industry. When I got signed it was the early 1990s and the revolutionary music of the day that got no-man signed bizarrely was ‘Madchester’ because we were using elements of the dance music in what we did, which was essentially a kind of experimental art pop but with samples of dance music. At the time, post-Happy Mondays and Stone Roses, it was a bit like at the time of psychedelia and the time of punk where the labels were absolutely desperate to sign bands in a particular field and I’ve always felt that sometimes, musical movements can accidentally generate innovation as well. If you think of people like Robert Fripp, Peter Gabriel, Peter Hammill, they are true individualists, but really they got signed on the whole psychedelic and progressive wave of the sixties and similarly quite a lot of artists signed on the wave of punk or new romantic, whether it’s Kate Bush or Thomas Dolby, a lot of fascinating artists became part of what was supposedly a more general wave of music.”

“It was a deliberate choice in choosing someone fifteen to twenty years older than I was because it was a very different experience in the music industry. When I got signed it was the early 1990s and the revolutionary music of the day that got no-man signed bizarrely was ‘Madchester’ because we were using elements of the dance music in what we did, which was essentially a kind of experimental art pop but with samples of dance music. At the time, post-Happy Mondays and Stone Roses, it was a bit like at the time of psychedelia and the time of punk where the labels were absolutely desperate to sign bands in a particular field and I’ve always felt that sometimes, musical movements can accidentally generate innovation as well. If you think of people like Robert Fripp, Peter Gabriel, Peter Hammill, they are true individualists, but really they got signed on the whole psychedelic and progressive wave of the sixties and similarly quite a lot of artists signed on the wave of punk or new romantic, whether it’s Kate Bush or Thomas Dolby, a lot of fascinating artists became part of what was supposedly a more general wave of music.”

Tim is in quite a unique position having feet in both the ‘musician’ and the ‘business’ camps…

“There is an element in that the business and the industry as a whole can psychologically affect your music in the same way that formats can do the same – I realise that I’ve always been obsessed with the nature of the album. Certainly, for the sort of music I make and music I like, there’s something about that classic forty to forty-five minute album sequence. It’s that sequence that appeals; the ‘right’ amount of listening for music of that intensity and you realise that about something that was dominant between then and the late eighties. If you think of the late eighties when CD came in, musicians tended to work to that format which is why I think you get quite a lot of overlong, bloated albums, that weren’t quite as disciplined or quite thought out. People were using the medium of CD to put on those twenty minutes of extra music that actually weakened the statement.”

Tim talked about being aware of this happening in the late eighties and early nineties and of…

“…many potentially great albums that didn’t work over a 75-minute duration. Bands were, in effect, almost forced to make what would be seen as double albums just to sell a commercial format.”

It seems a bit like filling the space ‘because it’s there’ negates both the quality and the experience of listening to music which in vinyl days gave the experience of listening, turning the record over, studying the sleeve and becoming immersed, resulting in a fuller and more fulfilling experience.

“I personally think the rise of vinyl sales is because if you think of now as the era of downloading and streaming, music almost becomes valueless and weightless with no element of ritual about getting a free stream from Spotify. With vinyl, there’s an element of ritual, of real care and attention that’s been put into these packages. Of course, the other thing is real value because although buying vinyl now is expensive it’s no more expensive in proportion to a wage packet than it was in the seventies. But it is the exact opposite – you have to buy it, you have to take more time over it and we found that when you’re putting together a vinyl album now compared to when I was first signed in the early nineties, the quality of the vinyl is much better, the quality of the art is much better and in some ways, which is a good thing, people are having to up their game now because of the demand people are putting on it. They want something of substance that has in some ways depth and in paying for it, they pay more attention that they would to a Spotify free stream.”

“I personally think the rise of vinyl sales is because if you think of now as the era of downloading and streaming, music almost becomes valueless and weightless with no element of ritual about getting a free stream from Spotify. With vinyl, there’s an element of ritual, of real care and attention that’s been put into these packages. Of course, the other thing is real value because although buying vinyl now is expensive it’s no more expensive in proportion to a wage packet than it was in the seventies. But it is the exact opposite – you have to buy it, you have to take more time over it and we found that when you’re putting together a vinyl album now compared to when I was first signed in the early nineties, the quality of the vinyl is much better, the quality of the art is much better and in some ways, which is a good thing, people are having to up their game now because of the demand people are putting on it. They want something of substance that has in some ways depth and in paying for it, they pay more attention that they would to a Spotify free stream.”

With the album concept, the obvious question to ask is how much Tim drew on his own experience? Maybe things he’d seen and heard in the music world…naturally, without naming names!!

“There is to a degree, but there are songs that are on this album which have been around as I’ve had this concept since about 2009 and I never thought I’d be able to realise it properly so a few of the songs ended up on Abandoned Dancehall Dreams and Stupid Things That Mean The World and one of them was The Great Electric Teenage Dream, and the interesting thing with that is that two relatively well-known musicians of my acquaintance said ‘That’s me!!’ and while it wasn’t necessarily them, there was an element of experience that they would have had that was in the songs. So it’s a combination of having an awareness of what happened to you at that time and also being close to musicians who’d had the best of their careers in the seventies and eighties. It was also fans that I met that like me when I was incredibly passionate about music in the late seventies and early eighties and I’d meet people who’d be in their late twenties and talking passionately about the revolution of the sixties and that nothing will ever be the same again – at 29 they seemed like they were already veterans of the First World War!”

“A couple of key songs were written in a more abstract way so it could be any cultural revolution, so it could be streaming or it could be dance music but a couple of tracks are actually about musicians that I know and the response that they had to the whole punk revolution and how it completely derailed their work and how they’d gone from being creative gods to being completely useless and unfashionable. I always remember reading interviews with Mike Oldfield and Eddie Jobson in the early eighties and at that point they were actually in their mid-twenties and seeing themselves cast aside as a relic! That ‘Year Zero’ mentality created in the press meant that some artists who were still doing creative things were sidelined. It’s not the full story as some artists from that genre probably had their greatest successes in that period – if you think of Pink Floyd and Genesis they went on to greater success. It was the sort of artists who’d be selling out the Manchester Apollo in 1979 and within about two years they’d be struggling at the Free Trade Hall.”

“A couple of key songs were written in a more abstract way so it could be any cultural revolution, so it could be streaming or it could be dance music but a couple of tracks are actually about musicians that I know and the response that they had to the whole punk revolution and how it completely derailed their work and how they’d gone from being creative gods to being completely useless and unfashionable. I always remember reading interviews with Mike Oldfield and Eddie Jobson in the early eighties and at that point they were actually in their mid-twenties and seeing themselves cast aside as a relic! That ‘Year Zero’ mentality created in the press meant that some artists who were still doing creative things were sidelined. It’s not the full story as some artists from that genre probably had their greatest successes in that period – if you think of Pink Floyd and Genesis they went on to greater success. It was the sort of artists who’d be selling out the Manchester Apollo in 1979 and within about two years they’d be struggling at the Free Trade Hall.”

And then as we’d mentioned Stackridge earlier on…

“they completely reinvented themselves and the two main songwriters became The Corgis and had an interesting career where they rode the wave and then artists like Gabriel, Fripp, Hammill and Bill Nelson, who completely anticipated the movement and were still true to themselves, but they were as valid in the eighties as they ever were so I certainly wasn’t referring to artists like that who completely understood what was happening around them and managed to manipulate what they did effectively. But it must have been devastating to certain artists to suddenly find that they’d been in a highly respected folk-rock band but could no longer even get a review in the music papers as they’d become persona non grata.”

There’s a line in You Wanted To Be Seen – “Your overwritten serenades, your sharp attack turned blunted blade” – which seems to be a significant one, a model of how overwrought wordage once considered the ultimate expression can turn into a bloated and self-possessed statement:

“…and I’m sure that must have psychologically affected a lot of the artists in that their work did lose its impact and become the blunted blade, and to an extent they lost the sense of themselves once success and respect had gone that in some way that can impact on the music. In the same way that I’m sure that someone who’s made a big living out of music and suddenly two million streams isn’t going to pay for that prosecco. The same too with artists who saw themselves as being vitally important and cutting edge and in 2017 are doing what is essentially a Golden Oldies tour playing to an audience who is the same age and you suddenly realise that you are the last blacksmith in town.”

“How long does that continue? In a sense it’s a sort of limbo of an older person singing a song to a much younger person in an entirely different era and the revolutionary spirit is absolutely crushed and you think about how that impacts on certain musicians who at one point would have felt that the world was theirs.”

The actual album theme and concept has been an ongoing project for a number of years. As mentioned earlier, some tracks have ended up on previous albums, which leads to a little treasure hunt in trying to guess what seems to fit!! Aside from The Great Electric Teenage Dream that he’d mentioned…

“On Abandoned Dancehall Dreams there was Songs Of Distant Summers which I’d rewritten for the new album and that was the only one I felt I had to have because it represented a kind of optimism, and the moment when the musician himself realises how much music meant and how much it lifted him from a fairly pitiful existence as a teenager – that transformative moment when you know that music means something to you. What else… Dancing For You, actually, because the idea of that was about the character reflecting on a hometown love who died effectively and it was about them then realising that music at that moment could do nothing. In that despair it had nothing to say. The title track to Stupid Things… was one and in that case that was almost the band emerging – a kind of Syd Barrett/Roger Waters relationship and I’m a big fan so it’s not a criticism – that burning youthful figure who propels the band through the early years is either sacked or goes mad and then you have a great career success. The song was partly about that sort of figure reflecting on the success and I did it in a fairly ambiguous way so it could be someone reflecting on an intense early relationship that went bad as well.”

“On Abandoned Dancehall Dreams there was Songs Of Distant Summers which I’d rewritten for the new album and that was the only one I felt I had to have because it represented a kind of optimism, and the moment when the musician himself realises how much music meant and how much it lifted him from a fairly pitiful existence as a teenager – that transformative moment when you know that music means something to you. What else… Dancing For You, actually, because the idea of that was about the character reflecting on a hometown love who died effectively and it was about them then realising that music at that moment could do nothing. In that despair it had nothing to say. The title track to Stupid Things… was one and in that case that was almost the band emerging – a kind of Syd Barrett/Roger Waters relationship and I’m a big fan so it’s not a criticism – that burning youthful figure who propels the band through the early years is either sacked or goes mad and then you have a great career success. The song was partly about that sort of figure reflecting on the success and I did it in a fairly ambiguous way so it could be someone reflecting on an intense early relationship that went bad as well.”

There may also be some speculation that Stupid Things That Mean The World could, in a much more literal sense, possibly refer to some of the crazy demands that musicians make that seem remotely trivial yet massively influence their moods – the ‘no blue M&Ms in the dressing room!’ type of thing…

“Well, I’ve seen something like that before! A musician who shall remain nameless backstage and there were various drinks; the band had specified 7Up and unfortunately they’d been given some lemonade – which may well have destroyed the performance!”

Looking through the album credits, the usual core band is in place – Colin Edwin, Stephen Bennett and Andrew Booker – but Bruce Soord plays guitar rather than Michael Bearpark.

“It was a personal choice although we’re still playing live with the band as it is; Michael’s a brilliant guitarist, incredibly original and abstract, but what I wanted for this album was a much more specific and melodic sound and someone who could soar in terms of solos and someone who was going to be connected to the material. Bruce was a great choice as he has a very contemporary understanding of guitar sounds, as well as a surprising knowledge of songwriters, guitarists and music, and I felt that he would do something as a songwriter and in keeping with the music. If I think of guitarists of the classic age, like Steve Hackett or Andy Latimer, they were profoundly melodic guitarists and in some ways Bruce is the same as he’s a songwriter as much as he is a lead guitarist and so that was it – I wanted something quite different for this album in terms of solos and I was pleased I asked Bruce as his performance was fantastic. It gave the album a different flavour which is what I wanted.”

Talking about the previous two albums, he described them as…

“…not so much companion albums but started as what I thought a no-man album would be and then developed the distinctive aspects. With this album and the nature of its concepts led me to want to do something new but also reflected the music of the musicians that the concept was about. That allowed me great freedom, despite working with a more limited set of sounds and in a different genre. Strangely enough, those sort of restrictions free you. Working to a conceptual frame, bizarrely enough, you find tremendous freedom working in a restricted area. It can actually be incredibly liberating and creative. One of the strange things about this album to me is that it was no less personal and no less emotional than what are regarded as my more personal lyrics. Certainly of late, I’ve thought of albums in grander terms so rather than writing individual songs it’s been about an idea. Abandoned Dancehall Dreams was a particular feeling rather than a story; it just makes the work more focused – strangely, the limiting yourself is a springboard to more intense creativity.”

“…not so much companion albums but started as what I thought a no-man album would be and then developed the distinctive aspects. With this album and the nature of its concepts led me to want to do something new but also reflected the music of the musicians that the concept was about. That allowed me great freedom, despite working with a more limited set of sounds and in a different genre. Strangely enough, those sort of restrictions free you. Working to a conceptual frame, bizarrely enough, you find tremendous freedom working in a restricted area. It can actually be incredibly liberating and creative. One of the strange things about this album to me is that it was no less personal and no less emotional than what are regarded as my more personal lyrics. Certainly of late, I’ve thought of albums in grander terms so rather than writing individual songs it’s been about an idea. Abandoned Dancehall Dreams was a particular feeling rather than a story; it just makes the work more focused – strangely, the limiting yourself is a springboard to more intense creativity.”

In terms of writing and recording Tim explained:

“I use any and every method, from me just writing basic songs, teaching it to the band, us playing live in the studio to sending files. On this album I did a lot of work with Stephen Bennet, who’s my keyboard player, and he has a very advanced chord vocabulary compared to mine. I have a very specific set of ideas and then he will try to realise those, send them to me, I’ll add comments and send it to people like Colin (Edwin), so on this record there was probably more file sharing than in the past where we played more live in the studio.”

So with the guests who appear on the album, there’s one name that stands out – the appearance of one Ian Anderson leads to the question of how he became involved and what sort of direction he was given…

“I guess I’ve really been blessed in that respect as even in the early days of no-man we were working with people like Robert Fripp, Steve Jansen and Richard Barbieri and Mick Karn and the thing you always have to do is be yourself. You have to believe that what you’re doing is giving them something as well as them giving you something; these people are tremendous musicians and stylists and you want them for specific reasons in your work, but you also have to hold your own in that field. When you’re in the process of recording, it’s never very starstruck, it’s always work. When we were working with Robert Fripp I remember giving him serious instructions and absurd instructions and then said ‘you do what you want to do’, so in cases of people like Colin Edwin and Robert Fripp you give a strong idea of what you want and do one take of what you feel is what the piece should have and generally you use bits of both. With Ian Anderson this was done remotely. I gave him the piece. I told him what it was about and what I was looking for and he did a wonderful job. Not being disparaging to anyone else, when his solo came in it was absolutly world class in terms of recording, performance and how appropriate it was for the piece. The starstruck aspect kicks in afterwards. I never get tired when I look at an album and there’s my name and then Ian Anderson or Robert Fripp or Mick Karn’s name! Certainly, when I was fourteen I wouldn’t have been able to believe it – but when you’re doing it, it’s always about what’s best for the song but afterwards when you reflect there’s always something shocking! One of my formative influences is Peter Hammill and for various reasons we’ve become friends and semi-regularly meet up to discuss the ills of the world, and when I’m there it’s a conversation between two opinionated friends but afterwards there’s still the sense of ‘did I just go for coffee with Peter Hammill?!’ The fan aspect never leaves you, nor does it ever overtake the working relationship.”

So yes, you can meet your heroes, and…

“…in 99% of cases people have been as nice and as decent as you hope they will be.”

Ian seems to have done a lot on the record, although all may not be what it seems;

“Actually, what’s funny about this is that Ian plays on Distant Summers, the last track on the album, and the reason I wanted him for that was that the song is all about the moment the musician becomes passionate about music and it transports him to another world, and of course when I was younger Ian’s work in Jethro Tull was one of the earliest things I liked so there was a real intentional point of having him. What’s interesting is that his style has very much evolved; it’s still distinctively him but he’s doing different things with that Ian Anderson flute sound. On Worlds Of Yesterday there is a flute solo that sounds EXACTLY like Ian Anderson and in fact it’s Kit Watkins who was in Camel, and a couple of the other solos which sound like Ian Anderson are either Kit or a guy called Andrew Keeling and both of them were huge fans of Ian’s work and they were both amused to hear that Ian would be on the album. I did think that quite a lot of people would think it was Ian Anderson on the other tracks but he’s only on the one!”

“Actually, what’s funny about this is that Ian plays on Distant Summers, the last track on the album, and the reason I wanted him for that was that the song is all about the moment the musician becomes passionate about music and it transports him to another world, and of course when I was younger Ian’s work in Jethro Tull was one of the earliest things I liked so there was a real intentional point of having him. What’s interesting is that his style has very much evolved; it’s still distinctively him but he’s doing different things with that Ian Anderson flute sound. On Worlds Of Yesterday there is a flute solo that sounds EXACTLY like Ian Anderson and in fact it’s Kit Watkins who was in Camel, and a couple of the other solos which sound like Ian Anderson are either Kit or a guy called Andrew Keeling and both of them were huge fans of Ian’s work and they were both amused to hear that Ian would be on the album. I did think that quite a lot of people would think it was Ian Anderson on the other tracks but he’s only on the one!”

Although on the one hand it might be doing a disservice to Kit and Andrew, perhaps they should take it as a compliment that their work is being mistaken as Ian Anderson.

The songs have some instantly recognisable ‘Bowness’ moments, but then you get Kill The Pain That’s Killing You, a musical departure which he describes as…

“…musically a piece I improvised with someone called Alistair Murphy who I worked with producing an album For Judy Dyble from Fairport Convention. We continued to write together and this was a one-off piece from around the time when I was writing songs like The Warm Up Man Forever and I was investigating some heavier rhythm driven things, so the song comes from that spirit. I could hear it going into somewhere fresh and was built from the rhythm upwards with Colin and Andrew doing a kind of intense Afro-Beat, and with the lead guitar I wanted something completely chaotic and free so you have Bruce Soord doing lead guitar but also David Rhodes doing the riff, so from the rhythm upwards it was coming together and it was a sort of combination thing I’d hear when I was growing up, like Talking Heads meets Philip Glass, but what came out was very different. Hopefully, your own personality comes over stronger than the influences and I think they really did in this case as it developed a life of its own musically and I was excited about where it was taking me. Lyrically it’s the moment on the album when the musician is completely lost and feeling useless so I used it as both directly about the fact that the musician’s marriage is falling apart and there’s maybe too much drinking and too much of an obsession with touring, but the family life is absolutely falling apart, and not only that, the sense of relevance is falling apart. It’s almost a prelude to You’ll Be The Silence – the place where the indulgence and the drink are taking him away from the vision. I was looking at using the song to explain why music had gone from being an overriding obsession to just a way of making money, so it’s that point in the album which is chaotic and where the life falls apart, both in terms of family life and career.”

“Like a lot of people, and I’ll throw Steven Wilson in this as well, I used to love making lists but also creating fictional bands…”

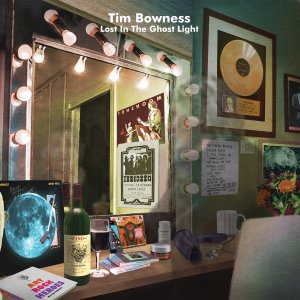

…was how Tim talked about the album art as looking beyond the music, it must have been quite fun creating this character and fictional band – the album covers, the setlists…,etc. There are lots of clues in Jarrod Gosling’s stunning artwork (a visual history of the subject in the concept) – the posters, signed album, age defying cream, red wine (‘Fino’), the vinyl and the CDs.

“In no-man Steven and I have already created incredibly successful jazz-rock careers for someone like Ben Coleman, along with about ten albums and their covers, so yes, it was great fun creating this fake career from 1967-2017, the twists and the turns. What was lucky was that everyone around me liked that concept and the fun part to it, and in fact, if the album was a serious investigation into what could happen to a particular musician of a particular vintage in the current day and age, putting together the lists and the album art was the fun part. I came up with a career history and all the album titles for the design and he got them perfectly in keeping with the eras they came from. We were even joking afterwards that we wouldn’t mind making some of these albums!”

“In no-man Steven and I have already created incredibly successful jazz-rock careers for someone like Ben Coleman, along with about ten albums and their covers, so yes, it was great fun creating this fake career from 1967-2017, the twists and the turns. What was lucky was that everyone around me liked that concept and the fun part to it, and in fact, if the album was a serious investigation into what could happen to a particular musician of a particular vintage in the current day and age, putting together the lists and the album art was the fun part. I came up with a career history and all the album titles for the design and he got them perfectly in keeping with the eras they came from. We were even joking afterwards that we wouldn’t mind making some of these albums!”

“If you look carefully you can almost see the ghost outline of the singer as well and yes, there was a lot of attention to detail and a lot of obsessive thought that went into it as you say, partly for the reason that we used to love poring through album details and credits, and also because it was incredible fun doing it – in some ways one of the best sleeves I’ve been involved in putting together.”

Back in November, there was an interesting collaboration with iamthemorning that shared the stage. Is that a future touring option or recording collaboration?

“It was really good actually and what was interesting is that we’re completely different musically in lots of ways but we fit because the mood of the music is similarly melancholy and reflective. What was great was that the two gigs, in Holland and London [TPA review of the latter], went down really well and both audiences seem to like each band – there was no competition whatsoever. A very appreciative crowd, a really good performance where they joined us and I joined them for two or three songs which worked out very well and my immediate thought was that we could do some new versions of the songs as one off recorded versions or as singles, so we have talked about it as it went so well. There’s a possibility of it happening again I think.”

Amidst thoughts and hopes of a Tim Bowness/iamthemorning collaborative tour heading north, possibly to the Warrington area (“the first gig I went to was the Warrington Festival…” he noted) before signing off, there was just a quick reminder to look out in the near future for a page on the Tim Bowness website about the fake history…

[And don’t forget, you can read Roger Trenwith’s review of Lost in the Ghost Light album HERE.]