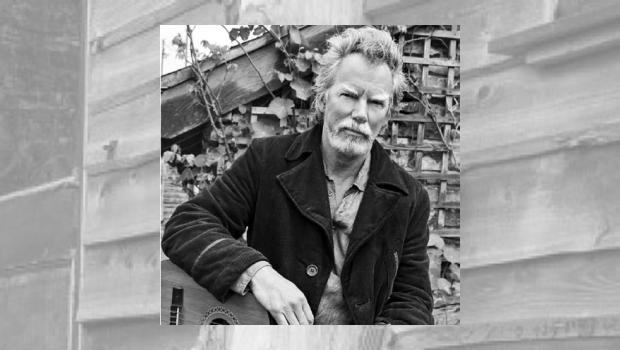

Long time Camel bassist Colin Bass has recently released his latest solo album, At Wild End, and TPA’s Jez Rowden took the opportunity to speak to Colin about the album and many aspects of his long and varied career. You can read Jez’s review of At Wild End HERE.

Hi Colin, thank you for taking the time to speak to TPA.

Firstly, what drew you to music in the first place?

The promise of escape into a better world. Music made everything larger, more meaningful. It fed my emotions, it filled me with wonder, excitement and hope. I couldn’t have put it into those words at the time, of course, but I’m thinking of when I was about five years old and my dad brought home a second hand record player and accompanying collection of 78rpm records. It was a diverse range of music but I remember just loving it all, from Felix Mendelssohn’s Fingal’s Cave to Slim Whitman’s Rose Marie. I loved to open the windows and broadcast the music to the street. Then my elder brother started to bring home more records: Elvis Presley, Fats Domino, Lonnie Donegan. Ah, the glitter and sparkle of electric guitars, drums and the throbbing of the bass. And then the sexual epiphany of watching my two female cousins jiving to Buddy Holly’s Peggy Sue in their print dresses, pony-tails a-swinging. What more do you need?

As a teenager you were already playing professionally, what was life like for you on the road in the ’60s?

Very unhealthy. Never having any money. Living on chip butties and amphetamines. Sleeping on a mattress wedged on top of the gear in the back of a van. Driving to Leeds to do a gig for 15 quid (which even in those days was shit money) But when you’re young you can put up with a lot of stuff. Or at least we could then. Who does that these days? Because there aren’t so many places to play. For example, I was the guitarist in a band called The Krisis. We had an agent (the bloke who cashed all the 15 quid cheques and left us to eat beans), who got us gigs around the country; provincial Saturday night dances and colleges and clubs, sometimes supporting bands like Pink Floyd, Yes, The Nice and other luminaries.

Very unhealthy. Never having any money. Living on chip butties and amphetamines. Sleeping on a mattress wedged on top of the gear in the back of a van. Driving to Leeds to do a gig for 15 quid (which even in those days was shit money) But when you’re young you can put up with a lot of stuff. Or at least we could then. Who does that these days? Because there aren’t so many places to play. For example, I was the guitarist in a band called The Krisis. We had an agent (the bloke who cashed all the 15 quid cheques and left us to eat beans), who got us gigs around the country; provincial Saturday night dances and colleges and clubs, sometimes supporting bands like Pink Floyd, Yes, The Nice and other luminaries.

Starting as a guitarist you soon switched to bass, what motivated this change?

I heard Jimi Hendrix play guitar. But I’d also always been drawn to the lower frequencies and I felt at home there.

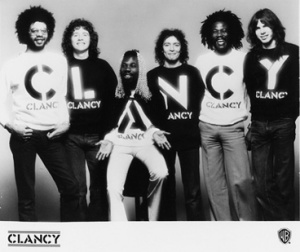

In your early years you played in a number of different styles, from the psychedelic rock of Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera through soul influenced pop with The Foundations and “pub rock” with Clancy. Were these changes of direction a natural progression based on a desire to try new things or the result of circumstance?

Circumstance. Curiosity. Serendipity. And the need to earn some money. But mostly the wanting to play something/anything, somewhere/anywhere. And I liked all the different styles of music. And it was a good time to learn about new things. And you could buy the Melody Maker music paper every week and look at the Musicians Wanted section of the classified ads section and see if there were any jobs going. I remember auditioning for Supertramp in a small Earl’s Court bedsit (pre-Crime of the Century). As you know, I didn’t get the job.

Circumstance. Curiosity. Serendipity. And the need to earn some money. But mostly the wanting to play something/anything, somewhere/anywhere. And I liked all the different styles of music. And it was a good time to learn about new things. And you could buy the Melody Maker music paper every week and look at the Musicians Wanted section of the classified ads section and see if there were any jobs going. I remember auditioning for Supertramp in a small Earl’s Court bedsit (pre-Crime of the Century). As you know, I didn’t get the job.

What was it like working with Steve Hillage?

I learned a lot from working with Steve. He’d just recorded the L album with Todd Rundgren producing and it had gone into the UK album charts. I think that was a bit of a surprise, so they had to get a band together quickly. Steve’s manager, Steve Lewis, had heard that my band Clancy had just split up so gave me a call. I went to meet Steve in his flat and had a jam. I got that job. He already had Clive Bunker on board and we started rehearsing the following week. It was fantastic playing with Clive. Brilliant drummer and a lovely, modest chap. We rehearsed every day for two weeks and then went off on tour. Steve was incredibly focussed. I loved playing those intricate arrangements. Fabulous melodies and killer riffs.

To many you will be most familiar for your work with Camel. How did you come to join the band?

I got to audition for Camel through the recommendation of their tour manager, Laurie Small, who had worked on some of the Steve Hillage gigs I did. I went up to a farm in Norfolk, where they were rehearsing in a barn. That was Andrew Latimer, Andy Ward, Kit Watkins and Jan Schelhaas. I remember they were rehearsing Hymn to Her. I hadn’t heard it before but I joined in and they seemed to like it. So that was nice.

Were you familiar with Camel before you joined?

Not really, I have to say. Aware of them, of course. In fact I remember Clancy supported them at the Roundhouse in London around Moonmadness time, I think. But we had another gig to go to and I only remember watching them for a few minutes.

What is your favourite Camel album of the ones you’ve been involved with?

I really love Harbour of Tears, not only because I helped Andy to mix that one but because it’s such a good piece of work with some excellent tunes and great set-piece compositions.

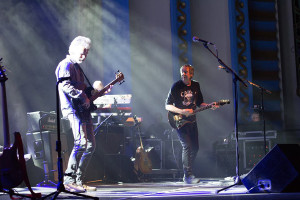

The unexpected re-emergence of Camel in 2013, after Andrew Latimer’s illness, delighted an awful lot of people – myself included. How did you feel when you received the call once more?

Well, Andy is a friend and I kept in touch with him throughout the period of his illness, thanks to Skype! It was of course wonderful to see him recover so well after such a life-threatening episode. As he got better he started to talk about doing something again, which I of course tried to encourage in my way but it was indeed a great moment when he said “OK, we’re going to tour again”.

The show in London at The Barbican in 2013 was extraordinarily emotional, as was the performance I saw in Bath earlier this year. Camel live has always been an emotional experience but these recent shows have been even more poignant after the sad loss of keyboardist Guy LeBlanc. That must have hit the band very hard.

Of course. We had all hoped that Guy would be able to do the 2014 part of the Snow Goose tour but his condition deteriorated quicker than expected at almost the last minute. The tour was about to be cancelled when dear Ton Scherpenzeel stepped in and literally saved the day. In fact, Ton came in for the last two days of rehearsal – and in the afternoon of the first day there was a power cut of several hours duration! So the first show was a bit shaky but it was in the Paradiso, Amsterdam, a home game for Ton, so he had to be good.

Of course. We had all hoped that Guy would be able to do the 2014 part of the Snow Goose tour but his condition deteriorated quicker than expected at almost the last minute. The tour was about to be cancelled when dear Ton Scherpenzeel stepped in and literally saved the day. In fact, Ton came in for the last two days of rehearsal – and in the afternoon of the first day there was a power cut of several hours duration! So the first show was a bit shaky but it was in the Paradiso, Amsterdam, a home game for Ton, so he had to be good.

Where did your interest in “World Music” start?

World Music? What’s that? OK, well something certainly started in 1974 when the Nigerian percussionist Gasper Lawal, joined my band at the time, Clancy. Hanging out at Gasper’s, I was introduced to the sounds of Fela Kuti and the Fuji drum orchestra of Barrister and the like, which after appraising some fine fruits of West African horticulture, came as a bit of an eye-opener. Particularly in regards to the construction of tight and funky bass-lines. Sometimes when there was a quorum of Lagos friends present, Gasper would hand around the percussion instruments – talking drums, shakers, darbukhas – and I would get the giant bass thumb piano: a large half tree-trunk with five flat bamboo sticks as keys. You can do a lot with five notes. It’s where you place them, it’s all about being part of a whole and keeping it moving. Anyway, that was a doorway to a wider world of music, for sure, and that education led me on to a lot of interesting things.

How did you become Sabah Habas Mustapha?

I really felt I was Sabah Habas Mustapha once upon a time. It was sort of method acting. I just had to put on the cheap suit, shirt with large collars bound by a hideous tie and I became this guy. A foreigner wherever he went and wherever he went he was strange and he thought that everywhere he went was a strange place with odd customs. I think it started in 1985. I was playing with a British/Ghanian band called Orchestre Jazira. The guitarist and drummer were Ben Mandelson and Nigel Watson. They were also having this funny little band who wore fezzes and masqueraded as a family of brothers and their uncle from a moveable state in the mythical Balkans called Szegereli. I went to see them, they were hilarious in a deadpan way and playing an intriguing pastiche of Greek, Albanian and Arabic music. When ‘Oussack’ the cellist left (later to become Ray ‘Chopper’ Cooper of the Oyster Band) I was asked to join. All the members were named after musical modes in arabic music: hijaz, isfa’hani, niaveti, etc etc. So after a period of time being the young ‘Neo’ Mustapha, Uncle, in a moment of inspiration, named me after the scale of Sabah and decreed also that I would be a walking palindrome, thus Sabah Habas Mutapha was born.

As part of 3 Mustaphas 3 you played music from a number of different traditions under the slogan “Forward in all directions!” What was the premise behind the band?

We were just interested in learning to play various songs and styles from around the world, gleaned from individual member’s record collections or their experiences travelling in other parts, particularly Africa and the Soviet-era Balkans. In order to play such a varied selection of styles – from sevdah to soukous to salsa – we masqueraded as the aforementioned Mustapha family, the house band of the Crazy Loquat club in Szegereli, situated at the crossroads to everywhere and a favourite hang-out for international lorry drivers, so we had to have a wide-ranging repertoire to survive. We were very entertaining with a deadpan comedic edge and we rocked too and did a lot of touring in the US, across Europe, in Japan and we even crept under the iron curtain they had in those days to play in Bulgaria and East Germany. We didn’t care.

We were just interested in learning to play various songs and styles from around the world, gleaned from individual member’s record collections or their experiences travelling in other parts, particularly Africa and the Soviet-era Balkans. In order to play such a varied selection of styles – from sevdah to soukous to salsa – we masqueraded as the aforementioned Mustapha family, the house band of the Crazy Loquat club in Szegereli, situated at the crossroads to everywhere and a favourite hang-out for international lorry drivers, so we had to have a wide-ranging repertoire to survive. We were very entertaining with a deadpan comedic edge and we rocked too and did a lot of touring in the US, across Europe, in Japan and we even crept under the iron curtain they had in those days to play in Bulgaria and East Germany. We didn’t care.

What was the most satisfying part of being a member of the Mustaphas?

To see people enjoying what we were doing even though they didn’t know whether we were serious or not.

Indonesia and its music appears to be very important to you. How did you get involved with this and how did you feel when your song Denpasar Moon become such a big hit in the Far East?

Now that’s a big question. I went on a holiday to Bali in 1988 and kept hearing this very melancholic gamelan music that really appealed to something within me. I found out it was actually music from West Java called Degung. So the following year I went to Java in search of the source, as it were. In Jakarta I was looking for music to license for some European record companies and I went to a cassette company that was putting out stuff I was interested in. The owner was a fine gentleman, now sadly no longer with us, called Mr Hartono. After arranging the license deal we fell to talking and, discovering I was also a musician, he offered me to record something in his studio. I was keen to play with some local musicians so he arranged a session the following week. While waiting I thought I’d better write a song to record and somehow this song Denpasar Moon came to me on the balcony of my hotel room. I imagined a mix of the melancholy Degung music and its typical heartbroken poetry with the groove of the Jakartan street music called Dangdut, as perhaps it might be sung by Engelbert Humperdinck – well, why not? It was a fun exercise: write a pure pop song! So I did the session, everybody thought it was a nice song and then nothing happened for a year until I went to Japan with Camel on the Dust and Dreams tour. I called up a guy I knew at Wave Records and played him the song and said I’d like to go back to Jakarta and do a whole album. I left it with him and when I got home there was a letter saying ‘a guy from Sony thinks your song could be a big hit, so we make your album soon, get in touch’. So I did go back to Jakarta and I made the album (thinking I might have a big hit). Meanwhile, unbenownst to me, Sony were recording the song with a young girl singer from the Phillipines called Maribeth. They used it in an advert for Sony hi-fis on Indonesian TV and then – bingo! She had the big hit. It then got covered by about 50 different Indonesian artists, translated into various regional languages and regional styles. So that was quite a surreal experience. It’s still an ‘evergreen’ song in Indonesia. I hope I get paid one day.

Now that’s a big question. I went on a holiday to Bali in 1988 and kept hearing this very melancholic gamelan music that really appealed to something within me. I found out it was actually music from West Java called Degung. So the following year I went to Java in search of the source, as it were. In Jakarta I was looking for music to license for some European record companies and I went to a cassette company that was putting out stuff I was interested in. The owner was a fine gentleman, now sadly no longer with us, called Mr Hartono. After arranging the license deal we fell to talking and, discovering I was also a musician, he offered me to record something in his studio. I was keen to play with some local musicians so he arranged a session the following week. While waiting I thought I’d better write a song to record and somehow this song Denpasar Moon came to me on the balcony of my hotel room. I imagined a mix of the melancholy Degung music and its typical heartbroken poetry with the groove of the Jakartan street music called Dangdut, as perhaps it might be sung by Engelbert Humperdinck – well, why not? It was a fun exercise: write a pure pop song! So I did the session, everybody thought it was a nice song and then nothing happened for a year until I went to Japan with Camel on the Dust and Dreams tour. I called up a guy I knew at Wave Records and played him the song and said I’d like to go back to Jakarta and do a whole album. I left it with him and when I got home there was a letter saying ‘a guy from Sony thinks your song could be a big hit, so we make your album soon, get in touch’. So I did go back to Jakarta and I made the album (thinking I might have a big hit). Meanwhile, unbenownst to me, Sony were recording the song with a young girl singer from the Phillipines called Maribeth. They used it in an advert for Sony hi-fis on Indonesian TV and then – bingo! She had the big hit. It then got covered by about 50 different Indonesian artists, translated into various regional languages and regional styles. So that was quite a surreal experience. It’s still an ‘evergreen’ song in Indonesia. I hope I get paid one day.

You’ve lived all over the world, where has been your favourite place and why?

My favourite place is now. And that takes place in North Wales. It’s very beautiful with forests and lakes and mountains to explore and a there’s new language to learn – which provides a bit of a challenge but offers manifold rewards in understanding a whole culture that knows it has to be vigilant to prevent itself disappearing.

The songs on At Wild End, named after the studio you have set up, are certainly filled with the rural feel of the setting. Is that something that occurred naturally?

Erm, I guess so! I don’t think I’m able to force something out, it has to be already in the air. But for the first time in ten years I felt I was able to devote time to putting another album together. I had a large writer’s block to climb over first but then once I had a couple of ideas in place the rest stared rolling out.

The release of At Wild End is the result of a successful crowdfunding campaign. How did you find the process?

Nerve-wracking at first but it ended up being a great experience. It was heart-warming to discover that there were actually people out there who wanted to help me make an album. So many people were so generous which was not only enabling, it was a real source of positive energy. It really brought everything into existence – both practically and aesthetically.

The use of brass on Walking To Santiago reminded me of the way it appears in the music of Big Big Train. Add in the harp and it has a sound all of its own. Although you use elements of folk, prog and numerous other genres, the songs do not remain rooted in the familiar. Was it your intention to make a largely acoustic album on your own terms?

Actually that song was the only one that had been around for a few years – with different lyrics. I knew there was something there but it wasn’t until I visited Santiago de Compostela that the theme really took shape. Although the lyrics in the second part are ascribed to three Camino pilgrims, I suspect they are somewhat autobiographical. As for my intentions, I just thought I’d let the songs grow out of an acoustic beginning, on guitar or piano. And that I wouldn’t try to write in any one particular genre. I’ve played and enjoyed a variety of musics in my so-called career so I wanted to allow myself to reflect all of that – although I feel I’ve only just scratched the surface. Come to think of it, that sums up my entire life.

Actually that song was the only one that had been around for a few years – with different lyrics. I knew there was something there but it wasn’t until I visited Santiago de Compostela that the theme really took shape. Although the lyrics in the second part are ascribed to three Camino pilgrims, I suspect they are somewhat autobiographical. As for my intentions, I just thought I’d let the songs grow out of an acoustic beginning, on guitar or piano. And that I wouldn’t try to write in any one particular genre. I’ve played and enjoyed a variety of musics in my so-called career so I wanted to allow myself to reflect all of that – although I feel I’ve only just scratched the surface. Come to think of it, that sums up my entire life.

There’s a hypnotic quality to We Are One. Did that also result from the surroundings in which you recorded?

Well the surroundings were certainly peaceful but there’s also – for me – something Javanese in that song with the pentatonic arpeggios played on the piano by the wonderful Kim Burton and the harp, played by the brilliant Sian James.

You have used the talents of a number of local musicians as well as some well known names from your past. You seem to have completely immersed yourself into your new surroundings as you did in your previous locations.

That is indeed a most interesting observation.

Up at Sheep’s Bleat is a poem set to music. Do you write much poetry?

Unfortunately I’m not constantly wandering the hills jotting down fabulous thoughts into a well-thumbed note-book but now and then a line or two fly into my mind and if I’m lucky I’ll remember them. Sheep’s Bleat was condensed from a series of four-line verses that I set myself to write over a few weeks, getting up early in the morning and playing around with the first impressions of the day whilst throwing the ball for the dog.

The reworking of Bob Dylan in Girl From The North West Country is highly appropriate and a lovely fit within the album. What inspired you to try it?

Well Dylan’s song was a re-working of an old Appalachian ballad so I thought I could re-work it too. I’ve always been a Bob Dylan fan since my schooldays and back then the Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album was another doorway into a wider world of music. Anyway, I wanted to do a song like that and take it from the Appalachian mountains to Snowdonia. So I did.

The more exotic sounds and world influences are still present, such as in the instrumental tracks Szegereli Eternal and Bubuka Bridge. What inspired these pieces?

The former is a small hommage to carefree days of musical discovery with the 3 Mustaphas 3 and the latter was inspired by the fabulous percussion playing of my friends in the great Sambasunda group from West Java. With their permission I constructed a groove out of some recordings I did with them in Bandung some years ago. People seem to like that one so I’m working on some more ideas like that. After all, the world needs more Javanese khendang drum grooves.

I see that Ben Mandelson of 3 Mustaphas 3 was involved on At Wild End. Do you think that 3M3 will ever return?

Ah, we don’t know where they went so we don’t know if they will ever return. Actually there was recently a quite reasonable request from the United States for the family to reunite and make people happy again but I don’t know if the offer meets Uncle Patrel’s exponential law of supply and demand for the presence of Mustapha – the longer people forget us the more expensive we become. We will see.

There’s a wistfulness to many of the songs on At Wild End, does that coincide with you yearning for a return to simpler times?

Ah, don’t we all, don’t we all? (he said wistfully).

The title track is a majestic thing that features the unmistakeable guitar of Andrew Latimer. Is this piece a summing up of what the album signifies for you?

Yes, it is.

And what’s next for you Colin?

I thought you’d never ask. In January I’ll be working on a collaboration with Sian James, the famous Welsh harp player and possessor of a golden Welsh voice, who played on three songs on At Wild End. We’ll be doing some of our own songs and some traditional songs of England and Wales. Our try-out gig will be at the end of January in my local chapel. In February I’m going to Helsinki to produce an album for a young lady named Maija Kauhanen. She’s a remarkable player of the kantele – Finnish zither-type thing – and she constructs slowly unfolding, captivatingly atmospheric and most beautiful compositions dripping with visceral Finnish singing, if that’s any kind of description. After that I’m hoping to do some live work with some of my good friends! Further I am not at liberty to divulge. Watch this space!

Thank you so much for speaking to TPA Colin, much appreciated, and good luck with At Wild End, it really is a lovely listen.

Thank you Jez.