2016 has been a tough year for many, but for Emerson, Lake and Palmer fans, the losses have been especially tragic. On 8th December, only two days after the following interview was conducted, legendary bassist and singer Greg Lake passed away aged 69, following keyboard virtuoso Keith Emerson’s unfortunate passing on 11th March. Despite the tragedy, bandmate and drummer Carl Palmer was able to keep a cool head as he wrote a statement about Lake’s death that very afternoon, saying “His music can now live forever in the hearts of all who loved him.”

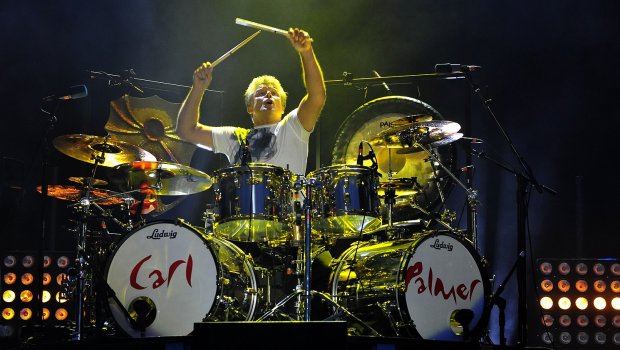

It’s perhaps a good thing then that this interview was captured just before the sad news, as the focus would surely have been shifted from the man himself. With a name that is so closely associated with Emerson, Lake and Palmer, it’s sometimes hard to remember that Carl Palmer has enjoyed much success outside the most revered of his bands. Already an experienced session drummer by his mid-teens, Palmer joined the Crazy World of Arthur Brown before founding Atomic Rooster. After the foray with ELP in the 1970s, Palmer also enjoyed a stint in Asia and worked with Mike Oldfield and others. He’s been credited with playing the first ever electric drumkit on the seminal album Brain Salad Surgery and sold 40 million albums with ELP alone. As a seminal drummer from the progressive era, it’s been an absolute privilege for TPA’s Basil Francis to speak to Carl, and we present the full interview below.

[To tie in with the interview we also have reviews of the 2016 reissues of ELP’s classic album Trilogy, Brain Salad Surgery and the Welcome Back My Friends… live album. You can read the feature HERE.]

Hello Mr Palmer, how are you doing?

I’m doing well thank you, how are you?

Very good thanks. As a drummer in my spare time, this is actually the first time I’ve ever interviewed another drummer, so it’s very special to have you as the first.

Good, I’m pleased to hear that.

I read that you’ve just finished your Remembering Keith tour. We were very sorry to hear of his passing here at The Progressive Aspect.

That was in the States, we finished about two weeks ago. We recorded a DVD on the 24th June at the Olympia Theatre in Miami, Florida. For that show, we had Steve Hackett playing on a couple of tracks as well as Mark Stein from Vanilla Fudge singing Knife Edge and Welcome Back My Friends…. We also had the Ida Choir from Florida singing Jerusalem and a contemporary dance group! The tour went very well, and I start again in February in South America.

Wow, interesting for an American choir group to sing such a British anthem. Are you touring the U.K. anytime soon?

Not until November 2017 I’m afraid. I’ll be playing on the 18th, 19th and 24th.

What’s been your highlight of the tour?

The whole tour has been fantastic. We’ve played in an awful lot of places and they’ve all been pretty good.

As a drummer, I’d love to know your origins in drumming. What was your first instrument?

I started playing the banjo when I was 7, and moved on to the drums when I was 11. My whole family was very musical, and we had professors of music too.

What inspired you to be such a speedy and technical drummer?

When I was 13 or 14, I used to travel down from Birmingham for drum lessons in London with a gentleman called Bruce Gaylor at the Boosey & Hawkes shop in Denman Street, by Piccadilly Circus. I’d already gone through several local drum teachers, and we decided through a very good friend of the family, Kenny Clare – probably the best drummer Britain ever produced – he suggested to my father that I go and meet with Bruce Gaylor. Kenny himself was unable to teach me, though he was my first choice. Bruce was visiting from America and spent about two years here. I was taught by him until he left Britain, which was about 14 months in total. With him I learned the ergonomics of drumming, the shortcuts, what you need to do and don’t need to – it turns out there are an awful lot of things you don’t need to learn to achieve the same goal. He’s definitely been the most inspirational teacher I ever had. In those 14 months, I must have learned about five years’ worth.

I wish I could have had the same sort of education. Who knows where I’d be!

I’ve had five drum teachers in my life: James Blades from the Royal Academy of Music, Gilbert Webster from the Guild Hall, Tommy Cunliffe and Lionel Rubin who were more local to me and of course Bruce Gaylor. There was also another in London called Max Abrahams, but I didn’t really learn much from him as he was teaching me to read music which was something I could already do. The point is, I’ve had a lot of teachers and each has given me something different; you can’t have one teacher to fit all.

I can see that it’s important to have a variety of influences. I don’t think I’ve heard the name Bruce Gaylor before, did he do anything else of note?

You wouldn’t have heard of him before. He’s what’s known in the drumming world as a ‘drumming geek’; he never played with anyone famous but because he was brought up in a wealthy family – his father was a diplomat and he travelled a lot – all he had to do was practice drums and that’s what they wanted him to do. He went on to become a well-known teacher in the New York area in the ’60s. He ended up living in New Zealand at the end of his life. The only time I saw him on television was when he was the backing drummer in a vocal group called the King Brothers back in the ’60s.

I believe shortly afterwards you enjoyed a stint in The Thunderbirds with some of the founding members of Colosseum.

The Thunderbirds was a backing group for Chris Farlowe with Albert Lee, Dave Greenslade, Bruce Waddell on bass and there was a brass section too. The story goes, I was playing at Birmingham Town Hall when I was 14 in a group called The King Bees in an all-night musical event that began at 7pm and finished at 7am. As quite a junior band, we were on first, ahead of all the other acts. The Thunderbirds had arrived early, Chris Farlowe had got the time wrong, but they got to see the last part of our set before they went on a bit later at around 10pm. It was during that evening that he said to me if I ever needed a job in London he’d give me a shot. When I left school, I travelled down in a van he sent for me and my drumkit, and had an audition with him and joined when I was 15.

Incredible, how old were you when you met Emerson and Lake?

I met Keith Emerson in 1967. I was playing in a very early incarnation of Fleetwood Mac. That may sound surprising, but I was only playing because Mick Fleetwood was ill. Peter Green had heard of me so John McVie called me up and asked me if I could fill in for Micky. The gig was at Battersea Art College and at the top of the bill was The Nice. That’s when I first said hello to Keith Emerson.

Was that what sparked your musical collaboration?

Not really. I subsequently became a Nice fan, I used to go and see them at the Marquee on a Monday. It was Keith’s manager at the time of The Nice who mentioned he should look out for myself. At that time I was in Atomic Rooster, a band I’d formed from the ashes of the Crazy World of Arthur Brown. At the time of the gig, we only said “Hi”. We weren’t even friends then. Our collaboration only sparked 3 years later.

How did it feel then, when you were called to audition with Emerson and Lake?

At that time, Atomic Rooster were doing incredibly well. I was quite happy to continue with that band. We had a strong cult following in Sweden and Germany as well as back home. It wasn’t something I had felt ready to leave. In fact, when I did leave I felt that I’d made a terrible mistake, because, before Keith, Greg and I had even recorded anything, Atomic Rooster had got into the charts without me, with their single Tomorrow Night. It was gutting to know I’d actually recorded a demo of that song with them, which they’d had to re-record without me for the album Death Walks Behind You. I personally thought I’d made a big mistake!

What changed your mind?

I had previously said to them that I only wanted to play in a trio when there had been talks of ELP being a four-piece band. After asking me twice, they told me what they could do for me, so I decided to try out with them and the rest is history.

Why do you feel it was important for you to play in a trio?

It’s just always been of interest to me. I enjoyed being in a trio when we backed Chris Farlowe and got rid of the horn section, Arthur Brown was a trio, Atomic Rooster was a trio, my band is a trio, Carl Palmer’s ELP legacy is a trio. For me as a drummer, everything tends to work better in a trio, there’s more space for the drums and a better atmosphere to hear them.

I like that it’s about the space to hear each instrument. Some bands, such as Yes, have more musicians to create a richer texture within the music, but I do quite enjoy when the music is about the core elements.

There’s nowhere to hide in a trio and if you get it right, like Emerson, Lake and Palmer, like Rush, like ZZ Top depending on the music you like, it works incredibly well and it is a fantastic thing. Another trio that really influenced me was the Jacques Loussier Trio, who were one of the first bands to make the crossover between classical music and contemporary, interpreting mostly Bach pieces in a jazz format, similar to Emerson, Lake and Palmer playing classical music in a modern contemporary format. There’s simply been a lot of great, great trios throughout music history.

Do you feel that Emerson, Lake and Palmer is where you really pushed yourself to your limit?

I still feel I’m improving today, and I’m playing the same music now better than I ever have done. Fortunately enough, I’m still improving, something that’s really important to me as an individual. The reason I ended Emerson, Lake and Palmer in 2010 at the High Voltage festival, was because I felt the band wasn’t playing as well as it should be. I’d have been quite happy if we could reach the standard we once had, but we didn’t reach that standard. Someone had to cut the apron strings, and I decided to do it. Standards of music and performance are very important to me. Keith was happy for me to do that, I’ve hardly spoken to Greg since, but he also knows it was the right thing to do. Sometimes it’s better to leave the dream intact rather than go around playing like has-beens; that’s really not what I’m all about.

In summary, I wouldn’t say that ELP pushed me as far as I could go because both of my feet and certainly my right hand are better than they ever were before. I look after my health and because of that, I’m still improving. I still think there are a few more years left for me to improve before I simply maintain the standard. If at any point I feel like I can’t reach that standard, you won’t be hearing about me anymore, I’ll just disappear.

As a younger fan of the group, I was only 19 when I saw you play at that High Voltage Festival in 2010, it was my only opportunity to ever see the band live so I’m glad that I took it. I noticed that you got off to a shaky start in Welcome Back My Friends, but by the end of the night you guys were booming and the fireworks and the knife in the organ really made it a special occasion. That being said, I can tell you’re quite the perfectionist and I can imagine it would have been difficult to tolerate the various slip-ups that happened that night. Was there anything that really stuck out in your mind about the event?

We had to rehearse music we’d written ourselves for five weeks beforehand, which tells you something was wrong. With his hand injury, Keith was only up to playing for half an hour really, so it was difficult for him to play the full 90-minute set. He was having such trouble playing the music that I suggested we sampled some of what he needed play and have that played in the background alongside his live performance. However, the minute you play with a sampler and a click track, prog music becomes a bit sterile; it needs to speed up and slow down. Keith tried his very best on the night, and as I said earlier, he was happy that I finished the group after.

I feel it was the right thing to do. Despite the slips, you played well on the night and the 40th anniversary was a great occasion to play and also to call it a day. It really left a lasting impact on the fans and everybody had a great time.

I had a great time myself, but at the end of the day somebody had to call it a day. Prog music or modern contemporary music has to be played as it was originally written. The moment you can’t play it like it was written, it doesn’t work. In orchestras it certainly doesn’t work like that; you might be a very talented violin player playing The FirebirdYou’d be surprised…

I never plan to fool them anyway. Take the Rolling Stones, you might not enjoy their music, but how they play now in their 70s is exactly as good as how they played when they were 20. That’s one of the rock blueprints for me.

At the High Voltage Festival, you also played with Asia, with the original line-up consisting of yourself, Steve Howe, Geoff Downes and John Wetton. The four of you came from a high pedigree progressive background in bands such as Yes and King Crimson, and yet the music of Asia couldn’t sound more different; instead we have commercialised AOR. I’ve always found the difference baffling.

I would say that you’re absolutely right, it is commercialised. On the first album, I’d say that tracks like Wildest Dreams, Time Again and Sole Survivor are quite proggy sounding tracks, but you also have Only Time Will Tell and Heat of the Moment which are the more commercial radio-friendly tracks. The whole of the first album was a summing up of a period of progressive music and condensing it from 10 to 20 minute songs into 4 to 6 minutes which we basically had to do to get onto radio. You have to understand that at the beginning of the ’80s, nobody was playing progressive music on the radio. You’d be lucky if you heard prog music now at 4am in the morning!

(Interviewer note: I can’t help noticing that the tautologous “4am in the morning” is a lyric from Moonlight Shadow by Mike Oldfield, who Palmer collaborated with the year before that song was released)

With MTV, music had really made a shift into being more commercial. We’d decided we wanted to go with that shift, and I think we made it work. I thought the first album was right, the second was OK, and after that, it went downhill, I can’t deny that.

When you were creating the music for the first album, was it difficult to approach short-form commercial songwriting when you were collectively used to more progressive long-form pieces?

It was basically a job where you had to take ideas that would normally occupy a fifteen-minute span and get that down to seven minutes, six minutes or even shorter. We did that on about three tracks and then after that we went for the commercial side of things to see if we could get on radio. We realised that those three songs I mentioned earlier, Wildest Dreams, Sole Survivor and Time Again weren’t going to be played unless we had a hit single.

Don’t forget, Emerson, Lake and Palmer also had a string of hit singles in America as well: From the Beginning, Still…You Turn Me On, Lucky Man, C’est la Vie. These are all the folk songs; they’re all the songs that basically aren’t prog. People call ELP a prog band, but we really had a lot of commercial music too. That’s why we were successful; we were able to tap into a lot of demographics, but when you listened to our albums there was much more to hear. That was the same premise that Asia was working on, that we need songs which will hit the radio, but we also need depth in our music. It’s a tall order, and sometimes you achieve it, sometimes you don’t.

It’s certainly a product of its time, and perhaps there’s something nice about that.

I mean, it is and it isn’t. If the band could have been like Led Zeppelin and just played blues rock, wouldn’t it have been great? That wasn’t the period we were in, unfortunately. Nevertheless, we managed to get to number 1 in America for nine weeks, we couldn’t have asked for more with that album. It was definitely difficult to follow up.

I just felt like drawing on something you said earlier, how ELP wasn’t all prog. My good friend Andy Tillison of The Tangent idolises Keith Emerson for his skills as a keyboardist, and yet says that he reckons only 40% of ELP output was ‘brilliant’, partially because the songs he didn’t like sounded nothing like the ones he did. He says though that the 40% was easily enough to make ELP one of his favourite artists. Was the inconsistency something that the band desired?

Any successful band needs to be quite eclectic. You can go one way and be like Led Zeppelin if you want, but even bands like Pink Floyd, they had singles, they had tracks that were meaningful on their own. Airplay is definitely important wherever you are. It depends on how far down that road you want to go, and as I say, ELP went down that road an awfully long way, a lot more than people actually think. We were known to be a prog band because we had the latest instruments and songs that had intros of up to ten minutes as well as our classical adaptations, but on the other hand, we had folk songs and singles that made it to the top ten in America.

Any successful band needs to be quite eclectic. You can go one way and be like Led Zeppelin if you want, but even bands like Pink Floyd, they had singles, they had tracks that were meaningful on their own. Airplay is definitely important wherever you are. It depends on how far down that road you want to go, and as I say, ELP went down that road an awfully long way, a lot more than people actually think. We were known to be a prog band because we had the latest instruments and songs that had intros of up to ten minutes as well as our classical adaptations, but on the other hand, we had folk songs and singles that made it to the top ten in America.

Was composing classical adaptations something that was new to you when you joined ELP?

It was something I was certainly interested in due to my fondness of the Jacques Loussier Trio who basically only played jazz adaptations of Bach. I was always exceptionally interested in doing that. We were looking into that side of life with Atomic Rooster. Keith Emerson had already dived into that with The Nice, so when we met, there was an instant synergy between us. One piece we both liked was Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. That, of course, made up our second album, a live album. It made radio history in America, where the full 23 minutes of it got played on the radio, something I witnessed as I was in the car coming from the airport to Manhattan, and it was played by DJ Scott Mooney for WMMR. We knew classical music was going to work although we didn’t realise it would be that big. It was something we did from the very first album beginning with side one, track one; The Barbarian by Béla Bartók.

You must be aware that you influenced many musicians back in the day to the point where you even had fantastically gifted bands such as Triumvirat nearly cloning your music. Have you ever listened to these bands?

I know exactly what you mean, but having not listened to those sorts of bands very much, I can’t really comment.

If you had to put your finger on one track or one album that you’re most proud of, what would it be?

I doubt if there’s any piece I could pull out of the hat. I’ve played with so many fantastic musicians in so many wonderful places, there’s not one that’s really more important than the other, as far as the music’s concerned.

I suppose if it was just an album, then Brain Salad Surgery for me was one of the most important albums that Emerson Lake and Palmer ever made. One of the most important concerts was in the Olympic Stadium with the orchestra where we had 78,000 people. That being said I still thought the show we did this year in Florida was amazing with the choir and the extra musicians I’d added to my band.

There are so many moments, I’ve been blessed, I’ve been lucky. I’ve been in three bands that have had number 1 singles, Arthur Brown, ELP and Asia. I’ve got so much to be proud of that it’s difficult to boil it down to one album or one event.

It’s good that you mention Brain Salad Surgery, as it’s one of my favourites too, which is why I chose to review the new reissue of it on BMG. I particularly enjoyed the demo tracks which I haven’t heard before. Did you have any thoughts you’d like to add about these reissues?

Don’t forget, whatever’s been done to the music, the music was great in the first place as far as I’m concerned. It was written well, it was recorded well, it was played well. Whatever’s been done to it, it’s just another version of a great piece of music. I don’t get overly excited, I just like the freshness that it brings to the table. If it helps people look at it in a different way or in a way in which they can connect to it more, then that helps too. When the piece of music is great, it’s great forever and it’s hard to mess that up. That’s why as a band we’ve been absolutely fine to hear new mixes or masterings of the music we’ve created.

What made you single out Brain Salad Surgery earlier when you said it was one of the most important for the band?

Possibly because it was the pinnacle of our creativeness. Let me put it in context; there were two albums that we found difficult to play on stage, the first being Trilogy, which was the first album where we did copious amounts of overdubs. Obviously, MIDI wasn’t born then so we couldn’t have two or three keyboards being triggered by one keyboard, we simply had to overdub. One of our policies as a band was we needed to make the backing track as three people sound so good that you could release it as an instrumental. With Trilogy we decided to do whatever we wanted to in the studio, but when we came to play it live we suddenly found there were too many parts for us all to play unless we’d carried auxiliary musicians, something frowned upon in those days, although there were bands doing that.

Then came along Brain Salad Surgery where we went even further again, and we never managed to play that all on stage. Now today we could, if we were all here and everything was working, simply because of the leaps and bounds that have been made in technology. So I’d say those two albums are very important, but Brain Salad Surgery would have been the most difficult album to play live at that time.

I’m glad I’m the one reviewing it then. Thank you so much for your time, and of course for your music.

I really appreciate that, thank you. Bye!

LINKS

Carl Parmer – Website | Facebook | Carl’s Art Website