EartH Hall, EartH, Dalston, London

Wednesday, 27th September 2023

This is my first time at EartH. Originally a dazzling 1930s Art Deco cinema – now, after close to a hundred years, a building that’s been round the block, been razored almost to its bones, survived to tell the tale and is now enjoying a third, fourth or fifth life, this time as an arts venue full of the bustle of possibilities. Outside, Dalston bustles in its own way, doing its usual low-rise-New-York impression. Street chat and deals, bar life, an ongoing pulse of people from all over the world; traffic as a torrent, sleep as an irrelevance. We pass through it all amiably enough, heading for our eyrie of artiness, a poorly-kept secret in the middle of the High Street. There are a lot of steps. EartH sits high above the Dalston streets, raised high up above London. One could feel a little cut off.

A location whose owners and punters clearly enjoy its rawness and time-scarred ambience, EartH has similarities to other London venues reclaimed from decrepitude, neglect or misuse – Wilton’s Music Hall, the Asylum Chapel in Peckham, or the cavernous revived Victorian theatre in Alexandra Palace. A once-grand location, it’s now stripped back to the crumbling brick and plaster and is only partially restored, so that your event takes place in the gritty ghost-shell of bygone entertainments. Ribbons of faded red and gold paintwork flock across walls and ceiling to the stage. Battered alcoves lurk in corners. Incongruous arrays of sound-speakers map grids against gnawed, flesh-coloured plaster. The seating tiers, their former seats long gone, ring the stage in concentric semi-circles, making the whole place feel like a Greek amphitheatre. There’s a strangely democratic atmosphere to this, despite the marshallings of the staff and bouncers. You park your backside on one of those tiers with the feeling that at any time you could rise to your feet and make a debating point.

Not that that’s likely to happen. Nearly seven hundred of us are sitting patiently in front of an empty stage (in a space where the hard-bitten textures scream “live event wear-and-tear is actually welcomed, folks”) waiting for Steven Wilson’s brand-new The Harmony Codex album to be played back to us, in full, through a full spatial audio technology rig: the aforementioned speaker arrays. Regardless of whether this is a hint of how things might be in the future (in a world hit by successive pandemics, unfinanceable band tours and visa-killing nationalism) and while it’s very much in tune with Steven’s frequently-trumpeted enthusiasm for enhanced sonic experiences, it’s new to me.

For sixty-five minutes, though, and in semi-darkness, this is what we do. Bar shrouded blocks and the indistinct shapes of electronic equipment, the stage stays empty. Not a soul in sight past the front row; not even a roadie. The full finished package of The Harmony Codex comes at us through a rig taller than a house, an apparent dispatch from nowhere.

If I’m making all of this sound anticlimactic, it isn’t. As played (and as heard for the first time), The Harmony Codex itself is impressive, even by the usual exacting Wilson standards. Notably it’s more instrumentally-based than many of Steven’s later works under his own name have been. It has songs, but few of them are tidy verse-chorus blasts, despite his recent leanings further into pop. It feels, in fact, more like a sort of process – a dense, river-like flow of music which pushes up songs as and when they need to appear.

The spatial audio is supposed to provide a “hemisphere of sound” for the ears and brain; and it does, and on this occasion it feels as if it’s arrived right on time. The album is almost as immersive as the technology it’s being fed through. Percussion rattles, additional vocal parts and keyboard ripples slide into earshot from either side, emboldening the existing stew of cinematic trip-hop atmospheres, prog architectures, Scandinavian noir-metallics, jangling jazz-fusion keyboards, late-twentieth century angst-rock, neo-vintage electronica and a fresh dose of forceful industrial gunnery (courtesy of Meat Beat Manifesto’s Jack Dangers, an old Wilsonian touchstone, now turned guest player). Bits of the music seems to emerge from little hatchways and trapdoors within the hemisphere. Sometimes, despite the impassive immobility of the looming sound rig, it feels like we’re watching the intricacies of a Victorian fairground organ at work, with distinctive auxiliary instruments embedded into the cliff-face of the main one. In flickering moments, we get a deeper insight into Steven’s enthrallment as regards the business of putting detailed soundfields together.

The Harmony Codex also feels a little more detached and musing than previous works. Each successive SW song album (solo, Porcupine Tree, No-Man or whatever) has been guaranteed to contain at least one individual song which makes my tears suddenly brim. This one doesn’t. Whatever its strengths, it also feels more quietly hard-bitten, more accommodating of its own mournfulness; slightly overwhelmed by the vastness of things and the weight of experience. Maybe it’s mutual middle-age creeping up on us, Steven and I: both of us adjusting to the way it takes a whittling knife to quick’n’easy sentiment, and how it shunts aside romance and ready answers in favour of accommodations and displacements. Him in shaping songs; me in how I’m hearing what’s sung to me. I don’t know…

I’m with friends and promising new acquaintances, and (fortified by beer and benevolence) that wide-demographic Wilson audience gives off a friendly impression as well. An hour, though, is a long time to sit in an unfamiliar place while watching nothing. I find a sense of loneliness setting in. A little detachment. It takes me a while to realise that this is in synch with the album itself. One of several inheritors of a particularly English stem of elegant and reflective sadness within pop, Steven has always had a taste for the melancholic, something generally evened out when it’s set against his interest in rocking out or in building a big ship. In The Harmony Codex, though, the melancholia and the musicality seem to be running in persistent, consistent sync: building each other up.

The scale of it – the detail, the carefully-plotted slabs of sound-shape insinuating themselves from either side of the audio, and this sense of elevated isolation – makes it seem as if Steven has opened up a brand new city quarter for us, full of buildings to gaze up at, lights in the upper levels. But there are no front doors to be made out; no keys to be used. Even the savage boom of industrial drums doesn’t land anything so personal or engaged as a punch to the throat. We’re on our own; and so are the melancholy penthouse dreamers suggested by this delicately monumental music. If I’m going to have to haul up that Pink Floyd tag which hangs round Steven’s neck like a perpetual albatross, I’ll at least point it towards what it’s hinting at this time. Not bluesy guitars or widescreen synthscapes, nor spliff-friendly meditations; but massy musical architecture delivering a dire warning. As with Wish You Were Here, the feeling of living amongst looming forces, structures and guilt complexes which have grown too large, too impersonal to let us function properly as human beings.

Part of the reason I’m thinking this, of course, is because I’m listening to the impeccably-crafted ghost-in-the-machine which an album becomes when it’s just sound, framing a vacant proscenium. Let’s see what part two of the evening offers.

The thirty-minute live set which follows the playback repeats a number of the Harmony Codex tracks, so there’s an immediate risk of having our first course served up to us again, warmed up. It doesn’t come across quite like that. In the low light, Steven stroll/swaggers onto stage; the same slight, elfin, delicately boned figure as always, with a hint of urban pimp-roll. For the first time since forever, he’s guitar-less, setting himself up behind a bank of keyboards, analogue synths and LED-flecked soundboxes. I know that Giorgio Moroder and the Berlin school of ’70s electronica were core influences at the start of his musical journey; so there’s an extra weight in seeing him, in mid-career, re-immerse himself in this so deeply and directly.

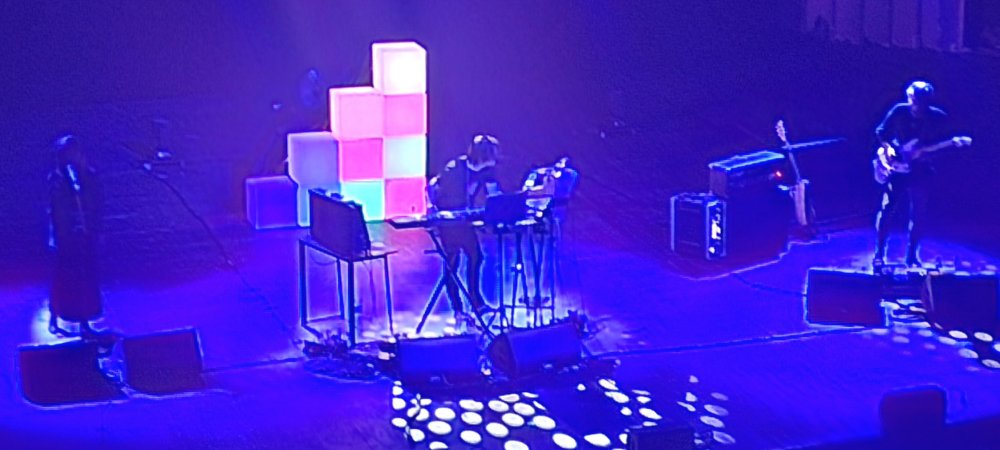

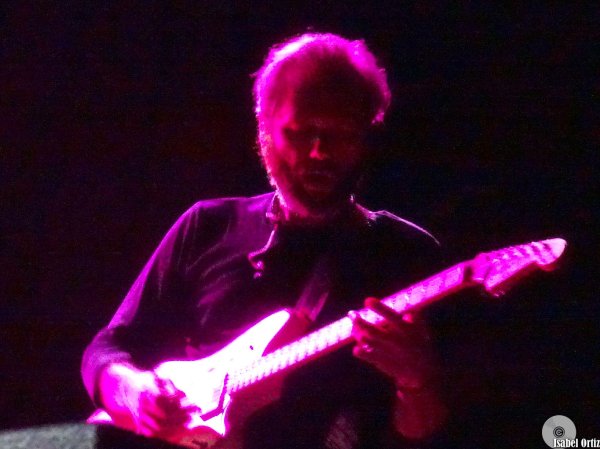

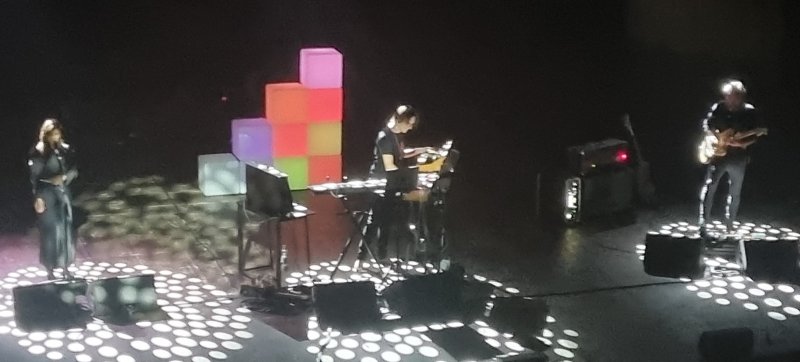

He doesn’t chat to us, nor does he offer any banter. He just gets right on with the job. Scurrying and flexing behind his consoles and racks, singing via a head mic, he looks like a canny 1990s rave act survivor, albeit in sober clothes. Former Lifesigns guitarist Niko Tsonev, who of course also played on the Grace For Drowning tour is also on hand. Looking tall as a crane, seeming caught permanently mid-stride, he arches and lobs swathes of powerful textural guitar into the music, placing them like chessmen made from smoke. Like Steven, he says not a word. Tonight, two proves to be silent company, with no rhythm section required. As they launch into a lengthy and confident improvisation, and as a plate-spinning confection of sequences, lines, beats and electronic strata persistently pours out from Steven’s multi-keyboards, no full band is needed.

For the evening’s title track, however, Steven’s wife Rotem is onstage to recite the litanies. “I gaze out across the millennia it took the lights from these stars to reach the earth. / I close my eyes / and breathe… / Are you dreaming me now? As your waking thoughts gradually take over, / as all dreams are ultimately forgotten / and lost.” Wrapped in a sheer black dress, her face obscured in the artificial gloaming, and possessing a voice of measured programmatic calm, she’s eerily like a virtual avatar. Only a small, concerned look sideways for her cue betrays the human being behind the microphone… and then she’s gone, leaving the men to work their way through the dissociative courtship music of King Ghost (from The Future Bites) with its Berlin electro-pulses, hip-hop tics and swooning falsetto.

The rest of the set is Codex material. The plaintive Economies of Scale, a piano ballad cut loose from gravity, with its apprehensions of brutal world market forces pressing through the ceiling. The Tricky-esque descending growl of Actual Brutal Facts. Finally, the seemingly endless electronica escalieration of Staircase, a concluding autopsy performed on the spiritual vacancy within the will to succeed. “Automaton drone, you’re lost with no phone,” Steven grits, “and the home you made your own can never be paid for…” Cold golden cubes of sound march out of the synthesisers, the guitar cuts deep and wide… and despite the barbs, there’s also a sense of rising. A rise, of sorts. Beautiful, but unsettling – like a man being painlessly, perpetually minced by his own gilded candelabrae, while plate-glass viewing windows close in on him like a gentle fist. “It seems I’m miles above the surface of the earth. / I can see across the whole of London and beyond… / I came here searching for something, / but I don’t remember what that thing is any more.”

It’s the capstone of an evening that’s made Steven seem strangely distant, enclosed in architecture rather than out front and hustling. Not cold, exactly, but becoming part of a measured rush; the hurtle of sequencing, build-up layers and pouncing arrangements taking precedence over hail-fellow-well-met, his reserved/plaintive vocals sailing above like a paper boat. In case this sounds dismissive, the man’s never been in better voice. The route to his approaching the circle of great singers has been a slow haul, but he’s close to it now. Fuller phrasing and timing have converged and come to him late in the game, but organically. Behind the belling, warping and thundering, behind the grand constellation of his music, it’s the voice – flitting into view as if seen between skyscrapers – that’s the gently captivating part of the evening.

The exit after Staircase is abrupt. Again, no word spoken. But as he leaves, Steven casts a bright, bird-like glance – even if it’s only for a moment – at his audience. A quick peek through the plate glass, it’s appreciative, and it’s friendly. The man in the high tower is probably OK.

[Photos by Isabel Ortiz and Mike Woods, used with kind permission.]

LIVE SETLIST

Improvisation

The Harmony Codex

King Ghost

Economies of Scale

Actual Brutal Facts

Staircase

MUSICIANS

Steven Wilson – Vocals, Keyboards, Synthesisers, Samplers, Sequencers, Rack-Mount Electronics, Programming

Niko Tsonev – Electric Guitars, Looping, Effects, Treatments

Rotem Wilson – Spoken Word Vocals (The Harmony Codex only)

LINKS

Steven Wilson – Website | Facebook

Niko Tsonev – Website | Facebook | Bandcamp