Sometimes you know before the conversation even begins that it’s not going to be a standard interview. Clare Lindley is one such person. A violinist, singer, composer, rock climber, and a fixture within Big Big Train (BBT) for several years now. A band that has developed such a layered and recognizable sound that every addition is, by definition, under scrutiny. That Clare Lindley has not only found her place in this, but also audibly makes her mark, is beyond dispute. Yet she speaks about it with a mix of matter-of-factness and a touch of irony, as if she’s still a little surprised by how everything turned out. An animated conversation about choosing the violin, the dark side of folk, the parallel between prog and mountaineering, and much more…

– Long arms, big hands

Her musical career didn’t begin with rock, let alone prog. Like many British musicians of her generation, it all began with subsidized music education at school, somewhere in Scotland. Choosing the viola had little to do with artistic vision and everything to do with anatomy. ‘They looked at my arms and hands and said: viola.’

The viola is larger, lower-pitched and richer in tone remained her home base for years. Only later, when Clare became increasingly immersed in Celtic folk, did the instrument prove to be a handicap. Folk music is written for violins, not violas. ‘On a viola, that becomes a kind of technical gymnastics, while the violinists remain carefree at the bottom of the neck.’ The transition to the violin ultimately felt inevitable. Today, Clary plays exclusively violin, even with Big Big Train, though a hint of that darker midrange still resonates in her playing.

– Folk, classical, Talking Heads

To initially label Clare as a “folky violinist in a prog band” is to do her a grave injustice. Her musical influences are broad, eclectic, and sometimes surprising. ‘I grew up in the eighties,’ she says, almost apologetically. ‘But there was also a tremendous amount of good music back then.’ Talking Heads, classical music, rock, pop, it all seeped in. And in her twenties, she lived with electric guitarists who were immersed in prog and heavy rock. The result is a musician who moves effortlessly between earthy folk and complex rock structures. ‘What looks like an earthy, folky person suddenly in a rock band,’ she says dryly, ‘is actually someone who can handle that perfectly well.’

– Where have all the violins gone?

The violin remains a rarity in prog rock. Of course, there are exceptions: UK, Kansas, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Solstice, but the instrument has never achieved the same level of familiarity as keyboards or the saxophone. Clare has her own, now well-substantiated theory on this. Electric guitars, she argues, have borrowed much of their expressive power from what violins have done for centuries: sustain, feedback, harmonics, fast runs. ‘Perhaps guitars are a kind of imitation of what a violin can already do without amplification.’ Viewed in this light, the violin isn’t an odd duck, but rather a forgotten primal source. It also explains why violinists in prog often play the long melodic lines, while guitarists provide the virtuoso fireworks. ‘A theory,’ she says, ‘but one I’m increasingly seeing evidence for.’

– No coincidence

It’s noteworthy that Clare succeeded Rachel Hall in both Stackridge and Big Big Train. Coincidence? Not really. ‘That’s how the music business works,’ she says. ‘You see someone play, you remember it, and one day there comes a moment.’ That moment came when BBT frontman Greg Spawton saw her perform. Spawton is known for his mental notebook, something he also did with Alberto Bravin. When Rachel Hall left, Clare Lindley was a logical choice. Not as a replacement, but as the next step. ‘I never felt like I was just joining.’

– Space in abundance

Big Big Train is a band where space isn’t a given. Arrangements are dense, layered, and rich. Yet there always seems to be room for another voice, another melody. ‘In prog, it’s not like one melody is enough,’ says Clare. ‘It’s like, oh, there could be another countermelody.’ The violin weaves through the whole, sometimes recognizable, sometimes distorted. Live, Clare uses distortion, with the result that the audience sometimes doesn’t know where a solo is coming from. ‘People look at the guitars. I love that.’ She doesn’t feel like a decorative element, but an essential part of the sound. ‘Otherwise, it would be unsatisfying for me, too.’

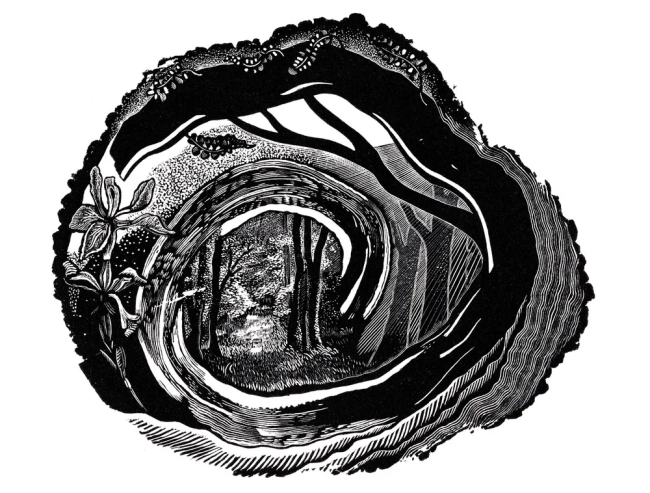

– Woodcut: Finally

With Woodcut, Big Big Train takes the next step: their first full-fledged concept album. According to Clare, it was mainly Greg Spawton who had been struggling with this for years. ‘A concept album can break a band,’ she says. ‘It’s a lot of work, and you want to get it right.’ The timing proved to be perfect. With Alberto Bravin on board, and a collective writing process, via Dropbox, a coherent musical arc slowly emerged. After intensive studio sessions at Sweetwater Studios in the US, one enormous task remained: writing lyrics. In five weeks, Clare and Greg wrote ten songs together. ‘That was intense,’ she says. ‘But also amazing.’

– Dark Folk

Clare’s contribution, The Sharpest Knife, stands out for its dark tone. Less pastoral nostalgia, more menace. For her, this isn’t an anomaly, but the core of folk. ‘A lot of folk is extremely dark,’ she explains. ‘Murder, poison, supernatural elements – it’s all there.’ According to her, this makes the song particularly well-suited for rock. ‘Something has to be slightly wrong. A bit of discomfort.’

– Nick Fletcher

The collaboration with guitarist Nick Fletcher on his most recent album, The Mask of Sanity, was quite surprising and intriguing. Nick Fletcher apparently just reached out, as a Facebook friend, and said, ‘I’d love for you to play on this album.’ ‘He had already written all the material or was finishing it. So the violin parts were already written. So I had to work on it a bit in my home studio. Almost like a session musician.’ It was quite a challenge for Clare, unlike anything she’d done before. And certainly not within the genre she normally plays on violin. Nick Fletcher plays a rather complex form of jazz-rock, fusion. That was difficult and a lot of work.

Outside of music, Clare Lindley is an avid rock climber. In South Wales and Cornwall, but also in Norway, France, and Spain. For her, climbing is more than physical exercise; it’s mental training. ‘It teaches you to silence that voice in your head. That voice that tells you something is too difficult. That it’s better not to try.’ Musically, she recognizes that mechanism immediately. ‘You have to dare to commit. Even if you can fail.’ A skill, she says, that changed her life.

– Epilogue

How Woodcut comes to life in a live setting remains shrouded in mystery for now. The desire for a complete rendition is there, as are the possibilities. What is certain: with Clare Lindley, Big Big Train has brought in not just a violinist, but a musician who dares to cut, chafe and sing. Exactly as prog was meant to be.

You can read Jane Lee’s review of the Big Big Train Woodcut album HERE.

LINKS

Clare Lindley – Facebook | Instagram

Big Big Train – Website | Facebook | Facebook (Group) | Bandcamp (InsideOut Music) | YouTube | X | Instagram