About two months ago, I received two reissues of Stackridge’s albums to review. One of them, Extravaganza, delighted me so much that I decided to go back and cover all five of Stackridge’s 1970s albums, reissued this year by Esoteric Recordings. To my dismay, I found that none of them lived up to the lofty heights of Extravaganza, which turned out to be a pretty unique album in the Stackridge catalogue.

Because it took me so long to review the first three albums, it was about a month between when I first listened to Extravaganza and when I finally heard it again to review it. While I was just as tickled by the Mellotron-drenched No One’s More Important Than the Earthworm and the three Zappa-inspired jazz-prog instrumentals found on Side Two, I found that I had forgotten a golden track that had added to the overall charm and whimsy of the album. That track was Happy in the Lord and I found myself playing it on repeat and singing it at the top of my lungs whilst doing the dishes. The upbeat rhythm, catchy chorus and subtle dig at old-fashioned English Christianity was a sumptuous concoction and I couldn’t get enough of it.

So imagine my surprise when I found out the song wasn’t written by Stackridge at all (despite perfectly blending in with the band’s signature whimsy) but was instead borrowed from a band I had never heard of called Fat Grapple. I tried to find what album this was from, but none existed. It was only ever released as a single by BEEB (an offshoot of BBC Records), and only a poor-quality vinyl recording of this was available on YouTube.

With so little literature about Fat Grapple available online, my journalistic instincts kicked in and I kept digging to try and find more of the story. I was especially interested in why Happy in the Lord had been written in the first place; was it written as a multi-faceted attack on the church or just a joke? And what did all of these metaphors in the lyrics refer to?

I was delighted to discover the songwriter himself, Phil Welton, actually responding to a YouTuber who had reacted to Happy in the Lord, and was beginning to explain the song’s origins. I contacted Phil and found that he was more than happy to recount his past and share music and pictures to present a full history of Fat Grapple, the obscure prog group that never made an album. Graciously, some of Phil’s former bandmates agreed to comment as well, including Lionel Gibson, and Eddie Jobson, who would go on to star in some of prog rock’s most celebrated acts such as Curved Air, U.K. and Jethro Tull but got his start at age 16 with Fat Grapple.

Hi Phil and Lionel (and Eddie!), it’s a pleasure to interview you. There’s precious little information about Fat Grapple on the Internet, so it’s a privilege to be able to add to the literature about the group.

Let’s start with some background. When was the band formed, and who was in the group at that time?

Lionel Gibson: While I was at Newcastle University, I was in a band called Steam Coffin (with Hammond organ player Michael ‘Goodge’ Harris, who went on to play with Arthur Brown and wrote some of the Galactic Zoo Dossier album [the 1971 debut from Brown’s Kingdom Come]). Then a crap blues band which did OK, then the whole Fat Grapple situation evolved, congregating in the student houses I was living in. We accepted Phil into the band purely because he was Nick Liddell’s mate.

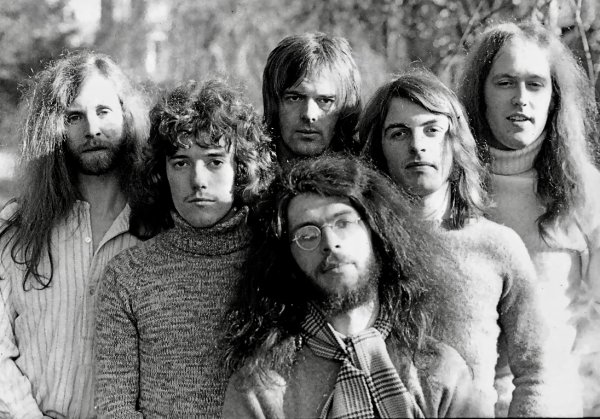

Phil Welton: The band was formed in July 1971. It was the reformation of a school band, The Warriors, who had all been at Barnard Castle School – Lionel Gibson (lead guitar), Nick Liddell (bass), John Saxby (vocals) and Rob Wilkinson (drums). They were all finishing Uni at that time. Lionel was in Newcastle and had accommodation they could move into and gigs they could play. (See below)

I had met a guy on the train up to my Uni (Dundee!) in 1967 and we had put a band together there. Nick Liddell was in it and Nick and I began writing together. By 1971 we wanted to continue working together and he put a good word in for me with his friends and they very kindly accepted me into the band.

Where did the name Fat Grapple come from?

Phil: Lionel had had a scratch band going at Newcastle which he had named Fat Grapple – he says inspired by two overweight friends who became a couple (Who knows?). When University ended they all left, as did Lionel’s housemates. The landlords did not seem to care one way or another so we were able to move into the vacated rooms (two little terraced houses) and play the gigs already booked in the name of Fat Grapple. We put together a set of covers in double quick time and slid seamlessly into the Newcastle scene. The plan was to work up our own repertoire of original songs and give ourselves a ‘proper’ name when we relaunched. However, we were pretty good as we were, so when we wanted to do that in September/October of 1971, Fat Grapple was already quite a strong name. So we kept it.

Lionel: The name Fat Grapple came when I was thinking about my two friends, both very fat, who had just got married, and I said to myself, ‘God, that will be a fat grapple.’ The name was born, very politically incorrect by today’s standards, but of course those were different days.

One of Fat Grapple’s claims to fame is the presence of a young Eddie Jobson, who I believe was 16 at the time he joined, but would go on to play for Curved Air, Roxy Music, Jethro Tull, U.K. and Frank Zappa, amongst others. How did he become drafted into the band?

Phil: We were quite ambitious musically and felt we lacked one element – violin/keyboards. We advertised in The Northern Echo – where else? – and one day a little chap in a school mac carrying a violin case approached the house and asked, “Is this where Fat Grapple live?”

Poor little lad. We brought him in and thought we’d have a listen and make sure he got home safe. We settled down and he began to play. Thirty seconds later the room had changed. We had to have this kid in our band. We went to dinner with his very nice parents and convinced them we were a safe group of guys for their boy. He was absolutely fantastic – keyboards too.

Was his talent clear from an early age?

Phil: It was certainly clear to us and he must have been very impressive for several years before we met him.

I read that he was poached by Curved Air after Fat Grapple opened for them. How did that split go down?

Phil: Curved Air were his heroes and, as luck would have it, they were the first band we supported at Newcastle City Hall, in September 1971. Eddie went to talk to them and played his hero, Darryl Way, his own version of Vivaldi, their hit single. That he played all the notes created by technical wizardry as well as by Darryl was not lost on the rest of the band. A year or so later, Darryl allegedly went off in a huff and they remembered Eddie. We were playing City Hall again one night and a call came through from them for Eddie. The rest is history. I believe Eddie was initially worried about leaving us but it was inevitable this would happen and he was quite right to go. We were, of course, very sad to lose him. However, by this time we had London management – the wonderful Barrie Marshall, whose company became Marshall Arts. Barrie found us an absolutely brilliant replacement in the shape of John Prior, violin, keyboards and flute, whose contribution was invaluable (John was an incredible arranger). So, happy endings all round.

Eddie: My music career started in 1971 with a group of 22/23-year-old university graduates who had formed a band in Newcastle called Fat Grapple. As a bold 16-year-old, I left home and moved in with them, learning — over the next year-and-a-half — not just how to survive in a struggling band, but how to question everything in life — politics, religion, social justice, art, poetry, drugs, money and, to some degree, even music itself — an intellectual, free-thinking mindset I have continued to benefit from throughout my life.

The band had almost excessively broad musical tastes, first introducing me to such talents as Joni Mitchell and to the outrageous brilliance of Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention — a group I could never have possibly imagined myself playing with only four years later.

Led by the excellent song writing of Phil Welton and the fluid musicality of guitarist Lionel Gibson, Fat Grapple were a folk-progressive-art-rock band…

Phil: Brilliant classification!

Eddie:) …who established themselves as the go-to opening act for many of the bigger-name groups that played in Newcastle. They were certainly musical enough to make an impact locally, but were clearly too eclectic for a full embrace by the music industry in London. I have learned over the years that demonstrating too much diversity can give the impression of being directionless — and, unfortunately, I think the band’s enthusiasm for Irish jigs, Russian-flavoured songs, Jewish wedding tunes and comedic ballads certainly contributed to that “too hard to categorise” issue for the labels.

Fortunately, despite their rejections from big concert agents and record companies, they maintained a positive attitude and remained generous and nurturing to me, always happy to showcase this young electric violinist — an important national exposure that would consequently launch a successful fifty-two-year career, for which I can only profoundly thank them.

Phil: Worth mentioning here that in 2019, Eddie was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Roxy Music. Congratulations, Eddie. Also, that we were not completely shut out by record companies and big concert agents. We played all over the UK, supporting very top-named bands. We caught various diseases in cities all over the nation and had a great time doing so. The last thing our management did for us was arrange for us to support Thin Lizzy on a tour of Ireland, which we foolishly turned down, scared of being attacked for being English. So, there was a lot of interest in us and we worked all over, including three gigs in Holland, but once we had a record deal with UA, they certainly found us ‘unmarketable’, to say the least.

How long was the band in existence?

Phil: We got together in Newcastle in July 1971. Once we had got our original material together we “launched” ourselves in October 1971 with a gig we arranged ourselves at the Newcastle University Gulbenkian Theatre. Some of the tracks you have heard (e.g. Vunchoo and the end of Hava Nagila) are actually recordings from that gig (actually the second of two nights we booked the Hall for). We went down pretty well.

We found our support act while in the Student Union when we heard a band practising which sounded highly unusual – The Alfred Mwazangi Coffeehouse Trashband Ensemble – who were essentially musical anarchists. They were magnificent and extremely entertaining.

We continued to get gigs and were playing something like two or three times a week. The gigs came from a Newcastle agent called Ivan Birchall, who turned up after a few weeks to find out what all the fuss was about. He happily continued getting us gigs. The best places I remember playing were Newcastle City Hall, The Newcastle Mayfair, The Sunderland Locarno and a fabulous place called The Viking, in Seahouses, a little town up the Northumbrian coast. Durham University was also a good source. They have several colleges and one year (1972) we played several of their ‘Summer Balls.’ And of course, working men’s clubs galore.

We naturally felt, as new bands almost have to in order to survive, that we were the best thing since sliced bread. We managed to be very entertaining, we had a sense of humour, including musically, and only once or twice did we hear the words, during the break at a working man’s club, “Well, lads, I’m going to give you five quid. You’re not quite what the committee expected, etc…”

We were looking for London management, and eventually, through a friend of John Saxby who was working for him, we had the great Barrie Marshall come along to a gig we played at The Roundhouse in Chalk Farm (a fabulous place), and he took us on. (The friend was Ed Bicknell, a fantastic drummer, at that time a booker for Barrie Marshall, who clearly felt his place was in management. He went on to manage Dire Straits with incredible success.)

How would you describe the band’s style? Happy in the Lord is not particularly ‘progressive’ but some other available recordings of the band, such as The Whaling Song and Requiem show a penchant for odd time signatures and complexity.

Phil: The band’s style was at once its blessing and its curse. We had at least five songwriters – Phil, John Saxby, Nick, Lionel and John Prior. Jon Gilston had a go while he was with us. Eddie had a lot to do with our opening and closing repertoire – Vunchoo, Hava Nagila, Czardaz, which occasionally caused riots – 50 lads at the South Shields Lions Boys Club ‘dancing’ to Hava Nagila in a kind of scrum – a health and safety nightmare. Each of us had his own unique style within which there was a lot of variety – John’s Song in Praise of Big-Hipped Women (Cock Rock, frankly), The Miner’s Song (a gentle jazzy song about his dad/his dad’s generation), and Don’t Mess with Moose (a humorous song about a young roadie’s martial arts prowess – Moose went on to be in the army; serious stuff).

This was great for a live rock/variety show but did not work in the end on an album. (Of which more later.)

Lionel: Influences are a tricky question because I listened to everything. John Peel a lot, Jimi Hendrix, Paul Simon – it was a pastiche of everything that was going, very eclectic. Lindisfarne; I was sponge-like, soaking up everything, psychologically absorbing things into my subconscious and then regurgitating stuff. I was not absolutely knocked out by any particular style.

Phil: A great example of us being open to all kinds of music.

In your opinion, why did the band never get the chance to record a full-length album?

Phil: We did, in fact, get a record deal with United Artists. Barrie Marshall managed a band called Man which already recorded for UA and Barrie had a good relationship with them. Other people were interested in us, notably the Robert Stigwood Organisation. We found their representatives far too slick, and preferred what we took to be the more relaxed, shall we say, hairy approach of UA. On reflection, I think this was a mistake. Robert Stigwood’s guys were at least interested in us because of what we did and how we sounded. What we didn’t know was that we were being signed up by UA mainly as a favour to Barrie Marshall (my conclusion) and we found ourselves being ‘looked after’ by a rather fringe chap involved in the publishing side of things, whose name escapes me. We got the impression we were not anyone else’s cup of tea. I think this goes back to our widely varying repertoire, which would make an interesting work of art, but not necessarily an album that the folks at UA would know what to do with.

We did record an album – though we were unable to finish mixing it – at Olympic Studios in June/July of 1973. One of my memories of that time is walking along a corridor and hearing Noddy Holder yelling “It’s Chriiiistmaaaas!!!!” at the top of his lungs – in July. We did this under quite difficult circumstances. We had a producer forced on us – a nice chap called Tommy Evans, a member of Badfinger. His producing credentials were odd in that he and his partner had made their song I Can’t Live if Living is Without You into a nice but unremarkable album track, whereas Harry Nilsson made it the best-selling single of 1972 worldwide. Tommy was making his own album during the week so got weekends and hung about during the week. Friday evenings consisted of the ambitious young engineer taking three or four hours to achieve a drum sound which had little to do with what we wanted. So, it was a very frustrating experience and we had little influence on what came out. We had no chance to mix the songs ourselves and were hoping for a chance to do so. UA were keen to listen to the tracks, we kept stalling and wanting to ‘make them our own’, so to speak. One weekend our management sent us off to the Cheltenham Festival (200 folk in a field) and played what we had so far to UA, who were dumbfounded. In the end, the only thing UA said they would do was put out the single, but we imploded before that could happen. The single eventually went out on BEEB records (the sounds of the ’70s production team really liked it).

As far as I can recall, the tracks recorded for the album were:

By Phil Welton:

Happy in the Lord – gentle satire on Christianity, Albion folk-rock?

My Friends and I – Folk-rock protest song.

Requiem – Prog rock despair over being dumped, various time signatures.

God Save the Queen – Bossa Nova version of the National Anthem.

By John Saxby:

Song in Praise of Big Hipped Women – Cock Rock with a great lead break by Lionel Gibson.

The Miner’s Song – Slightly jazzy, gentle song about the life and death of a Durham miner.

Don’t Mess with Moose – Very funny song inspired by our teenage roadie. Big rock harmony finish.

By Nick Lidell:

My Friend Billy – A beautiful song arranged by John Prior for harpsichord, string quartet and oboe, about an imaginary childhood friend.

By Lionel Gibson:

The Whaling Song – Epic rock sea shanty about whaling. Fantastic ‘storm’ lead break with big harmony vocals in the middle.

By John Prior:

Sextet in Ystrad Mynach – Jazz-rock instrumental inspired by the name of a little Welsh town or village we once drove through, just north of Caerphilly.

I mean, when you look at that variety of styles and consider that we had not yet had the opportunity to mix them properly, is it any wonder UA pulled the plug?

I’ll send you the tracks, Basil.

The Happy in the Lord single from 1975 remains the sole release by Fat Grapple. Were the songs on that single recorded live or in the studio?

Phil: Both Happy in the Lord and My Friends and I were recorded at Olympic as part of the album.

What made you choose those particular songs to be the A and B-sides? Were they the only songs short enough to fit?

Phil: I say, Basil, that’s a bit much! Those songs were chosen because Happy in the Lord was the track regarded by the band as a whole as the best bet for a single. To be fair, I think Stackridge put it out as a single eventually – in 1974? My Friends and I was, I think, chosen as the B-side because it was close to the spirit of Happy in the Lord. This indicates the problem we had as a band with widely varying styles in our material.

Did Stackridge ask your permission to cover Happy in the Lord?

Phil: Once a song is published anyone can use it and do whatever they like with it, as long as the writer gets the royalties, which I did.

How do you feel about their version of the song?

Phil: When I first heard it – I went along to Stackridge’s record company in 1974 and asked to hear it – I was absolutely appalled by it, since it was not remotely in the spirit in which I wrote it. I have come to appreciate what they did with it. I met them about 10 years ago when they played a local theatre in Deal, had a nice chat about it and got a ‘shout out’ when they performed it. I am grateful for the royalties, which, while not very much, were approximately 100 times what the single made me.

Did the Stackridge release end up bringing any fame your way?

Phil: None whatsoever. It did, however, pay the train fare for my girlfriend and I to go up to Dundee on the sleeper for her brother’s wedding, and six months later paid a couple of hefty utility bills.

As it is the band’s most famous song, and a lyrically beautiful one at that, I was hoping you would participate in a line-by-line analysis of Happy in the Lord. First of all, why did you write this song, and what does it mean to you?

Phil: It was the first ‘mature’ song I wrote – at least it was a major step change from previous songs – and I have always been extremely proud of it. I think it came out because I was visiting home to attend my sister’s wedding around Easter 1972.

The song has a very upbeat rhythm, which is further accentuated in the Stackridge version. I’m reminded of Mr. Blue Sky, but that song was, of course, written several years after Happy in the Lord. Was the musical arrangement for Happy in the Lord inspired by any other songs or artists?

Phil: If you listen to The Bedroom Tape – literally recorded in my bedroom doorway in the band house in Newcastle – that steady, padding kind of rhythm was how it was originally written and how we played it at gigs and on Sounds of the Seventies (twice – Pete Brown and John Peel). When we came to make the album for UA we had a producer rather imposed on us. Nice guy, Tommy Evans from Badfinger, mentioned before.

Somehow, in my absence, (wtf was I doing?) Tommy suggested and got the band to play the fast backing track. They all thought it was great and I was obliged to go along with it. This rather undercut the whimsy of it and indeed the subtlety of the lyrics. Worth mentioning that Stackridge heard the song in its original slower treatment, as recorded in a nice little studio in Worthing. But, of course, they turned it into their rather wilder, upbeat version, so maybe Tommy had something.

I really thought it could be ‘Number One in the UK and Number One in America’ (to actually quote me. Given how John Lennon got on a few years earlier I think if it had ever been released and got anywhere in the USA and people had actually understood it I might have been assassinated).

Didn’t heed my mother’s warning.

With God’s help, I surely shall prevail,

Be home in bed tomorrow morning.”

Phil: The first two lines came out of nowhere. The next two lines just followed along, making some sense of the first two lines.

Happy dawning

Happy in the Lord

Blessed morning.”

Phil: I’ve no idea where ‘Happy in the Lord’ came from, apart from following on from ‘with God’s help’. ‘Happy Dawning, Blessed Morning’ likewise turned up and followed the narrative.

Honouring our Great Creator

We’ll be back in church from time to time.

When Granny snuffs it eight years later.”

Phil: My sister was about to get married in church. We were NOT a church-going family. Granny did indeed die eight years later, but family was in Canada and I was visiting them and we could not afford to come back. this is a personal favourite lyric of mine, so cynical. But not really cynical, just how it was.

Happy Easter

Happy in the Lord

Kiss my sister.”

I noticed on the 2007 Stackridge live version, they changed this to ‘bless my sister’.

Phil: An Easter Wedding, during which I’m sure I kissed my sister, though the song was written a short time before. Stackridge probably didn’t have any idea about context, irrelevant to their version.

Goodness is our greatest treasure.

He will spread his bounty in our way,

Life and death in equal measure.”

Phil: I had been a Boy Scout. Good deeds were us. We valued them. God’s reward, however, seemed neutral on the subject. ‘His Bounty’ was whatever happened, good or bad.

Why should I despair?

Though he’s way above me he will love me till the end,

Till the day he comes to take me there.”

Phil: We are taught ‘God loves us all’, so nothing to worry about, and one day He’ll come and take us to his Heaven.

Whiter yet the Holy Umpire

He won’t get the green stuff on his knees.

He just holds the bowlers’ jumper.”

I’m fascinated by the metaphor here, which I’m not sure I quite understand.

Phil: Cricket. All white players, all dressed in white, everything whiter than white. God stands and judges. No help to anyone. Does not get involved (no grass stains from energetic fielding). Green stuff = money. He just assists the most dangerous man on the field to chuck a very hard ball at batsmen (by holding his jumper).

There was another chorus here, a la ‘Since my teacher taught me…’ – cut for time. That’s showbiz!

“One thing life has taught me / Kind of caught me unawares as I played Life’s Game. / Under this old sun there’s only One who really cares / Only one prepared to take the blame”. A fairly bald reference to Jesus.

Happy maiden

Happy in the Lord

Silly mid-on.

Happy in the Lord

Happy Christmas

Happy in the Lord

Happy New Year

Happy in the Lord

While we’re waiting,

Happy in the Lord,

For His Blessing.”

Phil: ‘Happy Maiden’: Maiden Over – The Virgin Mary. Silly Mid-On – Google it; the most dangerous fielding

position, willingly taken up by Jesus. ‘Happy Christmas, Happy New Year’, endless repetitive time marked by religious festivals. ‘While we’re waiting… For His Blessing’, which never really comes but is promised in the afterlife. And the violin and French horn take us out rather mournfully, while we are all still waiting, eternally, for his blessing.

Stackridge’s version ends with a sermon by a priest going berserk. Do you like this different ending? Do you think it fits with how the song was intended?

Phil: I think the way a song is intended is a personal thing for the songwriter. Once a song is out there, it is for other artists and their audiences to make new things from it. The berserk priest never entered my head when I was writing it. I was poking gentle fun at the C of E village green Christian tradition. Stackridge have a rather more iconoclastic approach to Albion, and I can see why the song appealed to them, and indeed why they treated it in that way.

On first listen, Happy in the Lord does sound very pro-church, and the jabs against religion are subtle. Have these subtleties gone over listeners’ heads before?

Phil: These subtleties aren’t very subtle really, if anyone actually listens to the lyrics. However, yes, people have assumed we are a ‘Christian’ band, or I am a Christian performer. I despair of the cloth ear of some listeners, but who am I to judge really?

How difficult was it to find that balance of writing a song that sounds happy but contains cynical lyrics?

Phil: It was not something I was making an effort to do. It just came out like that. It expresses pretty accurately my affection for the Story, my appreciation of the beauty of churches and other holy buildings (I would have been very happy to marry in the village church near my bride’s home. It was she who would not compromise – a very tough cookie) alongside my belief that we are pretty much alone in the Cosmos and it is our responsibility to make our lives as useful and meaningful as we can – in terms of the human desire for meaning – rather than invent a prescription for it.

Is Happy in the Lord your favourite Fat Grapple song, or are there others you think audiences should hear?

Phil: Happy in the Lord is a song with which I am very pleased and proud. I am pretty proud of quite a few other Grapple tracks in and of themselves, while appreciating that UA’s bafflement at what we thought we were up to was well founded. My other favourites include The Whaling Song (Lionel), Requiem (me), Don’t Mess with Moose (John Saxby), My Friend Billy (Nick, arranged by John Prior) and My Friends and I (me).

Did you end up joining any other musical acts after Fat Grapple?

Phil: I did not, apart from little local efforts and an attempt to do something in the early ’80s with Nick and his brilliant and very witty wife Linda, using my songs, her songs and I think his. We called ourselves ‘The Lentils’. Very much of the time.

I started a band with a friend after I retired – The Kismet Collective – which ended up with very similar issues to Fat Grapple: too many musical cooks, no particular identity. At the last gasp I stopped that and got together with just two other guys to do MY songs, MY way. The Karma Lights, which died due to Lockdown and my own depression.

Now Poetry is my thing – I put out a weekly 30-minute show, Our Poetry: The Music of Being Human, on Deal Radio – Wednesday evenings at 8.30pm.

How do you feel about the band’s legacy all these years later? Are there any regrets?

Phil: In a way, if I regret what happened with the Grapple (I do regret not ditching ‘Fat’ and simply calling us what we called ourselves – The Grapple) I would end up regretting joining it in the first place, which I could never do. It was the open-ended, overly democratic, exploratory nature of the band that I loved, and that was in the end its downfall.

I had a wonderful time for two-plus years and we supported some incredible bands. I doubt very much if I could have done anything like that without being in The Grapple.

I really regret us talking our way out of a tour of Ireland supporting Thin Lizzy in 1973, because we were scared of being attacked in Ireland because we were English. Of course, we would not have been. We’d have been welcomed, but that’s not how it felt in 1973.

I think that was the last straw for Barrie Marshall, who very gently and kindly (but very clearly and finally!) let us go in September/October of ’73.

With thanks to Phil, Lionel and Eddie for their time and insights.

LINKS

Phil Welton – Soundcloud